Dry eye disease is highly prevalent in the cataract population, and a growing body of research supports a healthy ocular surface as a prerequisite of cataract and refractive surgeries. Trattler et al found that more than 60% of routine cataract surgery patients had asymptomatic dry eye but that only 50% of these patients presented for consultation with central corneal staining.1 If the ocular surface is not pristine, IOL power calculations, measurements of toric IOL axis magnitude and alignment, topography, and keratometry can contain significant errors. Thus, failure to diagnose and treat ocular surface disease can result in suboptimal surgical outcomes.2,3

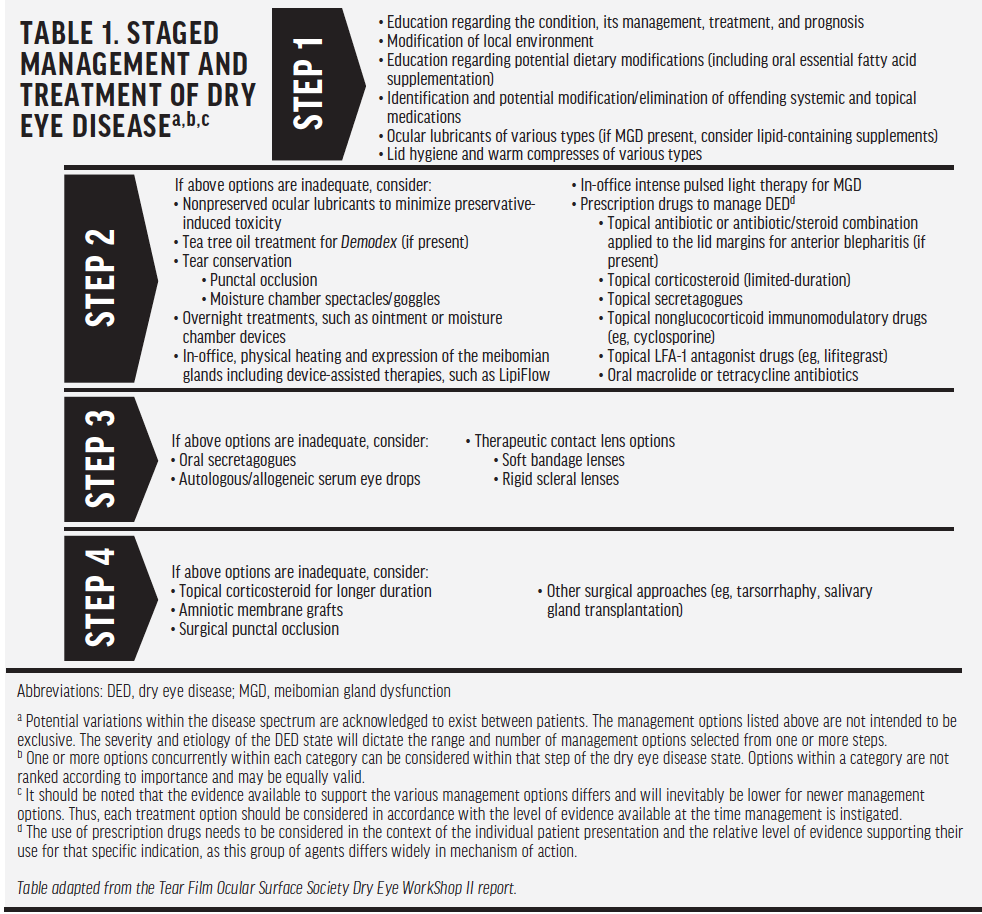

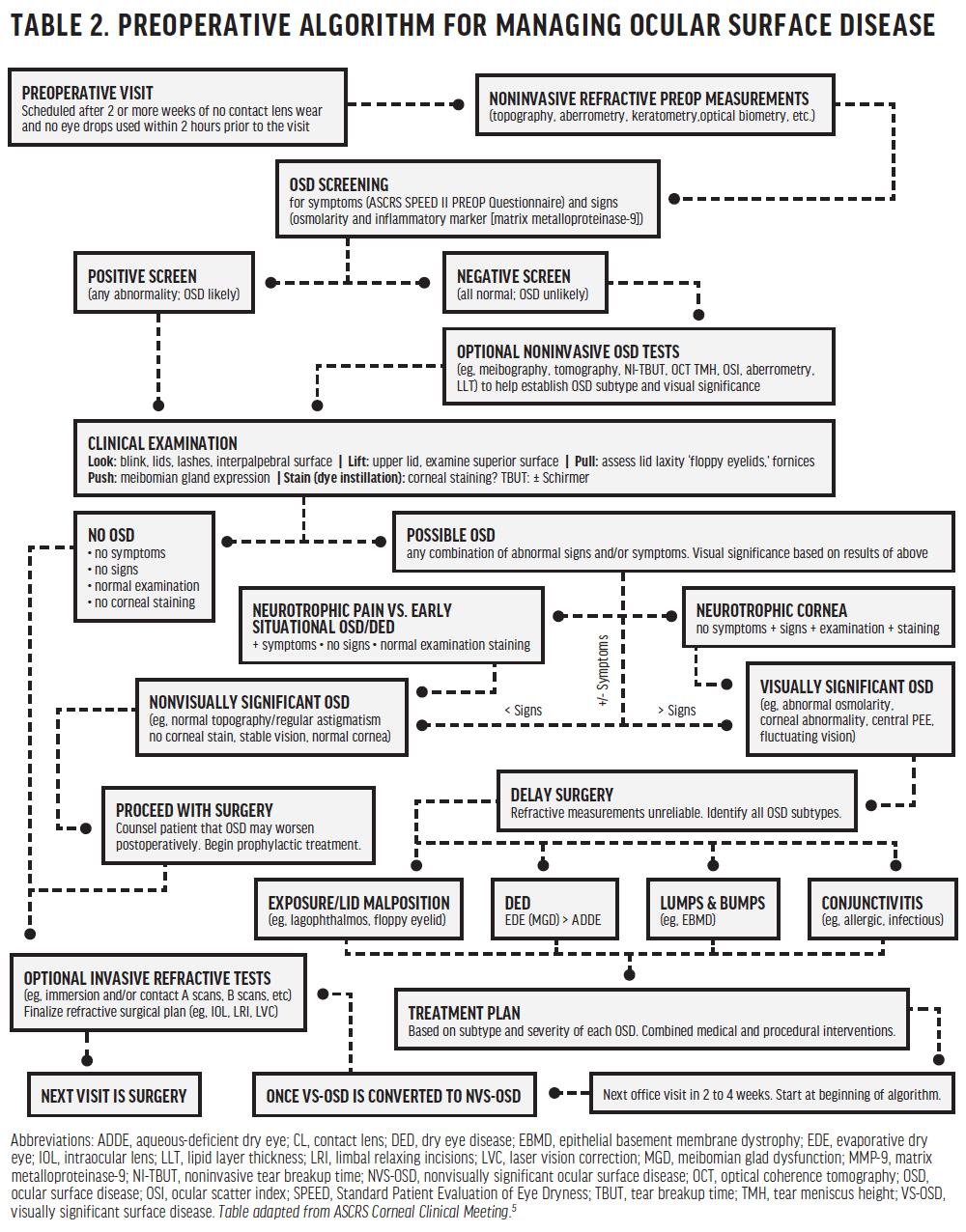

Because modes of practice vary greatly, from integrated practices to solo practices to group optometric practices to commercial settings, developing a standard of care for the preoperative patient can be a challenge. New guidelines from both the Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye WorkShop II report (Table 1) and the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS; Table 2) provide guidance on the diagnosis and management of ocular surface disease before surgery.4,5

PREOPERATIVE INTERVENTIONS

Patients may present to an optometrist with visual symptoms and complaints of worsening vision and night glare caused by progressive cataracts, or they may show up for their annual eye examinations and express interest in surgical freedom from glasses or contact lenses. The first step in delivering quality care is performing a comprehensive evaluation that includes the ocular surface. An unhealthy ocular surface can contribute to visual disturbances, affect the accuracy of measurements and any surgical plan, and even sabotage the patient’s recovery process. For example, goblet cell density has been shown to decrease after cataract surgery from exposure to both the microscope light and postoperative eye drops.6 The quality of the tear film would be negatively affected by a decrease in goblet cell density, which could negatively affect the patient’s quality of vision and recovery. Patients are best served when the ocular surface is optimized prior to their surgical consultations.

Once dry eye is identified, a treatment plan should be implemented before the cataract surgical consultation. Explain to the patient that you are making arrangements for his or her cataract consultation but that he or she will return to your office before that visit for preoperative dry eye management. Let the patient know that visits are necessary to optimize his or her eye and tear health to enhance surgical outcomes. When scheduling the patient for this visit, instruct him or her not to use any eye drops for 2 hours before arriving so that the osmolarity reading is accurate. This visit should include administration of a dry eye questionnaire (OSDI or modified SPEED) in addition to tear osmolarity and matrix metalloproteinase 9 screening. The modified SPEED questionnaire prompts patients to consider subtle causes of ocular surface disease such as recurring styes, a history of blepharitis, allergies, and contact lens intolerance.

The ASCRS guidelines recommend that eye care providers look, lift, pull, and push when performing a preoperative dry eye examination (Table 2).5 Following these steps will help you to identify an unstable tear film, corneal insults, blepharitis, floppy lids, mild anterior basement membrane dystrophy, conjunctivochalasis, and meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD). Once identified, ocular surface disease should be categorized as visually significant or not. Patients with visually significant disease require counseling because many surgeons will postpone intervention until the disease has been treated. A multifaceted approach is most effective to stabilize the disease quickly.

Patients appreciate and want good care and good refractive outcomes with ocular surgery. The engagement of primary eye care professionals at this stage in the perioperative process helps improve patient understanding and compliance with treatment for the long term.

Remember: Inflammation is the root cause of dry eye disease, whether it is evaporative or aqueous-deficient in nature. The number of available treatments continues to grow. Current options include topical cyclosporine 0.05% (Restasis, Allergan), topical cyclosporine 0.09% (Cequa, Sun Ophthalmics), lifitegrast ophthalmic solution 5% (Xiidra, Novartis), and various corticosteroids. However, both aqueous and evaporative components should be addressed simultaneously. Treatment of underlying blepharitis with in-office microexfoliation and identification and treatment of MGD with LipiFlow Thermal Pulsation (Johnson & Johnson Vision) or other in-office meibomian gland clearing treatments, such as TearCare (Sight Sciences) or the iLux MGD Treatment system (Alcon), and the use of at-home cleansers and heat can effectively optimize the ocular surface.

If a patient’s dry eye is severe enough to require second-line intervention, then an ophthalmic consultation should be considered because the patient’s choices for refractive or cataract surgery will be limited even if his or her disease state is controlled. Furthermore, if Salzmann nodules or anterior basement membrane dystrophy have created an irregular ocular surface, these issues should be addressed surgically before the patient undergoes cataract or refractive surgery.

POSTSURGICAL TREATMENT

Cataract and refractive surgery both disrupt the tear film. The extent of disruption depends upon the procedure or procedures performed, the quality of the presurgical tear film, patient compliance with prescribed dry eye therapies, and the ocular insult sustained from the use of postoperative eye drops. Continuing and modifying the dry eye regimen to optimize the patient’s visual outcome is the critical last phase of the process.

FOR BEST OUTCOMES TREAT BEFORE SURGERY, NOT AFTER

Patients presenting for cataract and refractive surgery tend to have a high incidence of undiagnosed dry eye disease. By addressing the dysfunctional tear film perioperatively, you ensure that these patients achieve the best possible outcomes and receive the best possible care.

1. Trattler WB, Majmudar PA, Donnenfeld ED, McDonald MB, Stonecipher KG, Goldberg DF. The prospective health assessment of cataract patients’ ocular surface (PHACO) study: the effect of dry eye. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:1423-1430.

2. Woodward MA, Randleman JB, Stulting RD. Dissatisfaction after multifocal intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35(6):992-9973.

3. Epitropoulos AT, Matossian C, Berdy GJ, et al. Effect of tear osmolarity on repeatability of keratometry for cataract surgery planning. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(8):1672-1677.

4. TFOS DEWS II report. Tear Film & Ocular Surface Society. www.tfosdewsreport.org/report-tfos_dews_ii_report/36_36/en/. Accessed December 17, 2019.

5. Starr CE, Gupta PK, Farid M, et al; for the ASCRS Cornea Clinical Committee. An algorithm for the preoperative diagnosis and treatment of ocular surface disorders. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(5):669-684.

6. Oh T, Jung Y, Chang D, et al. Changes in the tear film and ocular surface after cataract surgery. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012;56(2):113-118.