Navigating the care of patients with cataracts and underlying retinal disease requires careful assessment and consideration, and optometrists play a crucial role throughout the process. In this article, we explore the complexities involved in patient selection for cataract surgery, the role of diagnostic imaging, IOL options, and potential postoperative complications.

- Knowing when to refer a patient for cataract surgery first requires assessing the relative effects of preexisting retinal disease and cataracts on visual function.

- Patients with active diabetic macular edema must be referred to a retina specialist for treatment before undergoing cataract surgery.

- Although IOL selection is ultimately the decision of the surgeon, optometrists play a vital role in educating patients about their options.

PATIENT SELECTION

Determining the appropriate time for a cataract surgery consultation requires assessing the relative effects of preexisting retinal disease and cataracts on visual function. One example is in the case of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). If a patient’s retinal morphology has remained largely intact with minimal atrophy, but they have experienced a gradual decrease in vision due to worsening cataract, then recommending cataract surgery is straightforward. However, in cases of advanced or foveal-involving AMD, the decision can be more nuanced because these patients may have already lost central vision, such that the additional visual effects of the cataract may seem inconsequential.

In such cases, cataract surgery may not confer sufficient benefit, but it is worth considering, as patients often still report subjective enhancements, even if traditional outcome measures are not achieved. These may include reduced glare, clearer color vision, and better overall visual quality, which can considerably improve a patient’s quality of life after surgery.1 Moreover, cataract surgery can enhance peripheral vision, potentially improving orientation and mobility and reducing the risk of falls by up to 70%.2 Patients may also find low vision aids more beneficial after cataract surgery.

Patients with diabetes may have variable outcomes after cataract surgery. Those with uncontrolled diabetes may benefit from preoperative fluorescein angiography and OCT to assess the extent of their retinopathy and risk of developing postoperative macular edema. Patients with active diabetic macular edema must be referred to a retina specialist for treatment before undergoing cataract surgery.

IMAGING CONSIDERATIONS

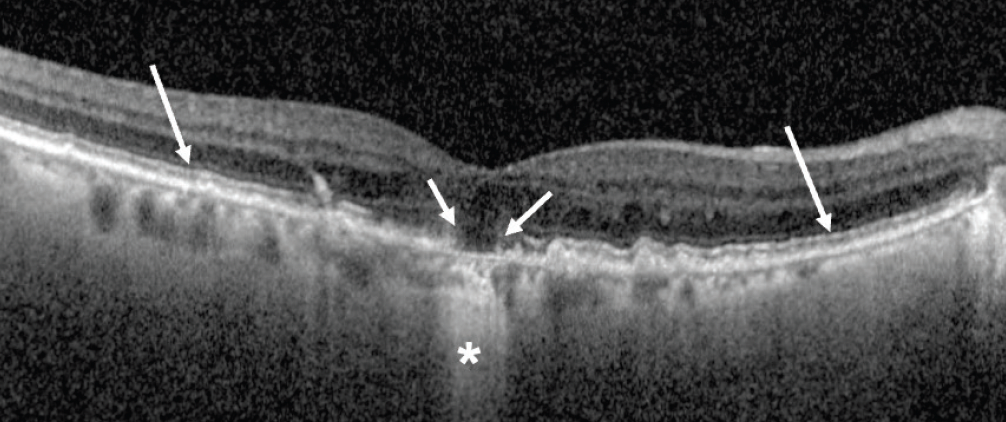

Predicting postoperative visual acuity improvement in patients with underlying retinal pathologies is challenging. OCT scans offer valuable insights into macular health, allowing optometrists to identify abnormalities not visible on retinal examination that may influence surgical outcomes. One region that closely correlates with visual acuity is the outer retina, particularly the ellipsoid zone (EZ), which is the junction between the inner and outer segments of the photoreceptors.3 An intensely hyperreflective EZ band, especially if located in the fovea, is a strong predictor the patient will have a good outcome.3 Conversely, patients with a broken EZ band will likely have permanent visual dysfunction; improvement post-cataract surgery may be modest (Figure 1). An exception would be patients with large pigment epithelial detachments who have a solid EZ band but still experience significant distortion and metamorphopsia, despite improvement in visual acuity.

Figure 1. OCT of a patient with disorganized subfoveal inner/outer segment junction, otherwise known as the EZ band (short arrows). Note the intact perifoveal EZ band (long arrows). Also present is significant subfoveal retinal pigment epithelium loss, as indicated by the hypertransmission/reverse shadowing defect into the choroid (*), another indication of poor visual prognosis.

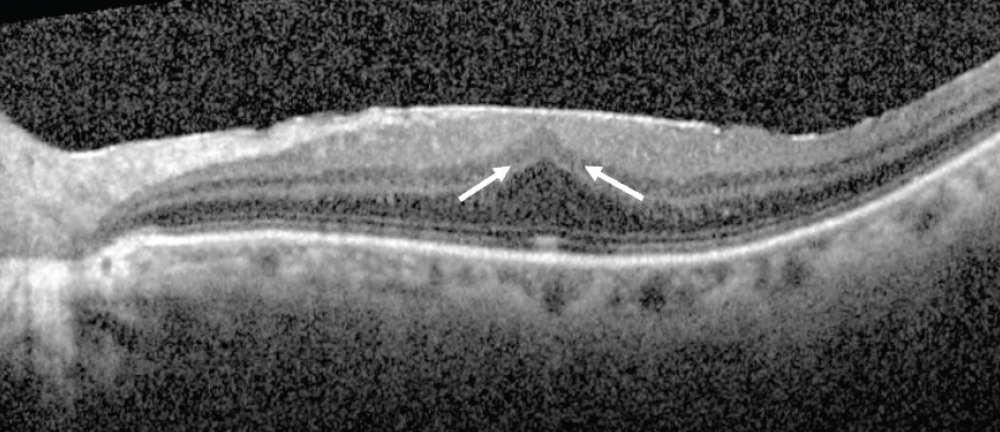

Epiretinal membranes (ERMs) can be seen on OCT imaging but are oftentimes mild, without significant distortion to the foveal anatomy. For patients with this finding, cataract surgery alone can be offered with a good visual prognosis. Patients with loss of foveal contour or alteration of the mid and outer retinal layers may benefit from a combined surgical approach to remove the cataract and peel the ERM.

An OCT sign that is predictive of a poor visual prognosis in patients with an ERM, even after a combined cataract surgery and membrane peel, is the presence of ectopic inner foveal layers (EIFL).4 EIFL represent extreme loss of foveal contour, as the inner plexiform and inner nuclear layers are drawn over the fovea (Figure 2).4

Figure 2. OCT of a patient with a severe ERM demonstrating EIFL. Note the presence of continuous hyporeflective and hyperreflective bands (arrows) extending from the inner nuclear layer and inner plexiform layer across the fovea.

IOL SELECTION

IOL selection is a critical decision-making process, especially for patients with preexisting retinal pathology. Although the ultimate choice lies with the surgeon, optometrists play a vital role in educating patients about their options. Multifocal IOLs offer reduced dependence on glasses but may cause dysphotopsia and reduced contrast sensitivity, particularly in patients with compromised macular function.5 Extended depth-of-focus IOLs present an alternative for patients with retinal pathology, although concerns persist regarding their effect on contrast sensitivity and overall visual quality in this patient population.6 Monofocal and toric IOLs are generally considered to be safer alternatives, offering predictable visual outcomes without compromising contrast sensitivity.7

POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

The postoperative period following cataract surgery demands meticulous attention, particularly for patients with preexisting retinal conditions. Optometrists play a critical role in monitoring for and managing potential complications.

Cystoid Macular Edema

Postoperative pseudophakia cystoid macular edema (CME), also known as Irvine-Gass syndrome, is one of the most common causes of vision loss after cataract surgery.8 Fortunately, incidence of visually significant CME is generally accepted to be less than 1% in patients without risk factors.8 Still, it is important to perform OCT if a patient who has finished their postoperative drops suddenly experiences a decrease in vision without a known reason. Postoperative CME typically responds well to topical corticosteroid and NSAID therapy (Figure 3).9

Figure 3. OCT of CME that developed in a patient 6 weeks postoperatively (A). Resolution of CME was observed after 4 weeks of therapy with topical prednisolone 1% and ketorolac 0.5% (B).

Certain preexisting retinal conditions can amplify the risk of severe CME. Patients with diabetic retinopathy, ERMs, or retinal vein occlusion (RVO) face an elevated risk of postoperative CME. The relative risk of developing postoperative CME can be up to five-times greater in patients with ERM and up to 30-times greater in patients with RVO.10 The postoperative duration of the topical NSAID and corticosteroid can be tailored to the clinician’s risk assessment of the individual patient.

Retinal Detachment

The incidence of retinal detachment (RD) after cataract surgery is about one in 500 within the first year after surgery. Factors such as young age, high axial myopia, or absence of a posterior vitreous detachment slightly increase the risk.11 Analysis of Intelligent Research in Sight Registry data reveals that the presence of lattice degeneration increases the risk of developing RD or retinal tear after cataract surgery.11 Vigilance during the postoperative period for these high-risk patients is crucial.

No Substantial Risk of AMD Progression

Concerns regarding the exacerbation of AMD following cataract surgery have long been raised.12 One potential hypothesis for this linkage is that inflammation induced by surgery can upregulate the complement pathway, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of macular degeneration. However, according to a recent analysis of data from the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2, patients with AMD can undergo cataract surgery without fear of worsening their disease.13

THE BENEFITS OUTWEIGH THE CHALLENGES

Cataract surgery holds the potential to significantly improve functional vision in patients with preexisting retinal conditions, albeit amid unique challenges and considerations. Optometrists and retinal specialists play a pivotal role in ensuring optimal visual outcomes and enhancing the quality of life for these patients.

1. Bilbao A, Quintana JM, Escobar A, et al; IRYSS-Cataract Group. Responsiveness and clinically important differences for the VF-14 index, SF-36, and visual acuity in patients undergoing cataract surgery. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(3):418-424.

2. Feng YR, Meuleners LB, Fraser ML, Brameld KJ, Agramunt S. The impact of first and second eye cataract surgeries on falls: a prospective cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1457-1464.

3. Sakai D, Takagi S, Hirami Y, Nakamura M, Kurimoto Y. Use of ellipsoid zone width for predicting visual prognosis after cataract surgery in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Eye (Lond). 2023;37s(1):42-47.

4. Mavi Yildiz A, Avci R, Yilmaz S. The predictive value of ectopic inner retinal layer staging scheme for idiopathic epiretinal membrane: surgical results at 12 months. Eye (Lond). 2021;35(8):2164-2172.

5. Alio JL, Plaza-Puche AB, Férnandez-Buenaga R, Pikkel J, Maldonado M. Multifocal intraocular lenses: an overview. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017;62(5):611-634.

6. Thananjeyan AL, Siu A, Jennings A, Bala C. Extended depth-of-focus intraocular lens implantation in patients with age-related macular degeneration: a pilot study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2024;18:451-458.

7. Swampillai AJ, Khanan Kaabneh A, Habib NE, Hamer C, Buckhurst PJ. Efficacy of toric intraocular lens implantation with high corneal astigmatism within the United Kingdom’s National Health Service. Eye (Lond). 2020;34(6):1142-1148.

8. Grzybowski A, Sikorski BL, Ascaso FJ, Huerva V. Pseudophakic cystoid macular edema: update 2016. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1221-1229.

9. Heier JS, Topping TM, Baumann W, Dirks MS, Chern S. Ketorolac versus prednisolone versus combination therapy in the treatment of acute pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2000;107 (11):2034-2038;discussion 2039.

10. Henderson BA, Kim JY, Ament CS, Ferrufino-Ponce ZK, Grabowska A, Cremers SL. Clinical pseudophakic cystoid macular edema. Risk factors for development and duration after treatment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(9):1550-1558.

11. Morano MJ, Khan MA, Zhang Q, et al; IRIS Registry Analytic Center Consortium. Incidence and risk factors for retinal detachment and retinal tear after cataract surgery: IRIS registry (Intelligent Research in Sight) analysis. Ophthalmol Sci. 2023;3(4):100314.

12. Klein R, Klein BE, Wong TY, Tomany SC, Cruickshanks KJ. The association of cataract and cataract surgery with the long-term incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(11):1551-1558.

13. Bhandari S, Vitale S, Agrón E, Clemons TE, Chew EY; Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. Cataract surgery and the risk of developing late age-related macular degeneration: the Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 report number 27. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(4):414-420.