Postoperative endophthalmitis is the most potentially devastating complication of cataract surgery. It consists of a severe inflammation that involves both the anterior and posterior segments of the eye. The disorder is caused by an infection that can progress rapidly, potentially leading to serious and irreversible vision loss.

Although the complication is rare, every optometrist involved in the postoperative care of a surgical patient must be alert for this potential emergency and prepared to act accordingly.

THE SIMPLE FACTS

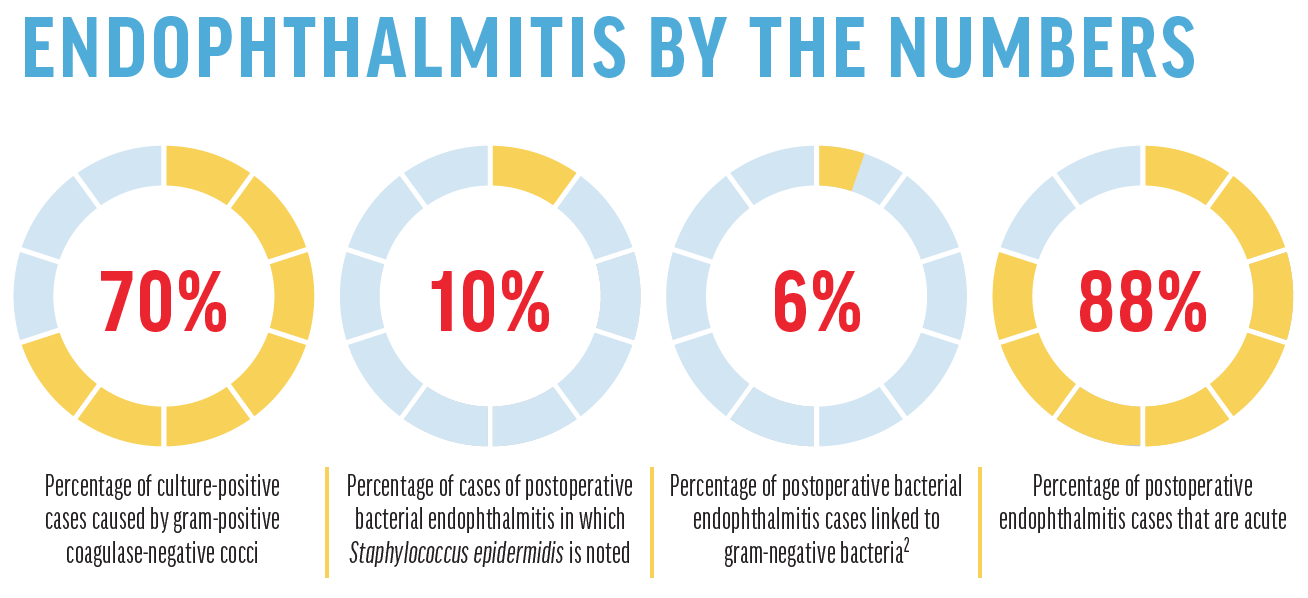

Postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis has been reported to occur in between 0.04% and 0.2% of cataract surgeries.1 The primary etiology is a patient’s own ocular surface and adnexa, with gram-positive coagulase-negative cocci (mainly Staphylococcus epidermidis) accounting for 70% of culture-positive cases. Staphylococcus aureus is noted in 10% of cases, followed by Streptococcus and other isolates. Gram-negative bacteria (ie, Pseudomonas) account for only 6% of cases but can be particularly virulent and devastating.2

Anything that increases exposure to a patient’s own normal flora generally increases the risk of endophthalmitis. This can include blepharitis, conjunctivitis, or nasolacrimal duct abnormalities. In addition, longer surgery or surgical complications, including poor wound construction, capsular rupture, vitreous loss, and contamination of instruments or breaching of the sterile field in the OR, can increase a patient’s risk.

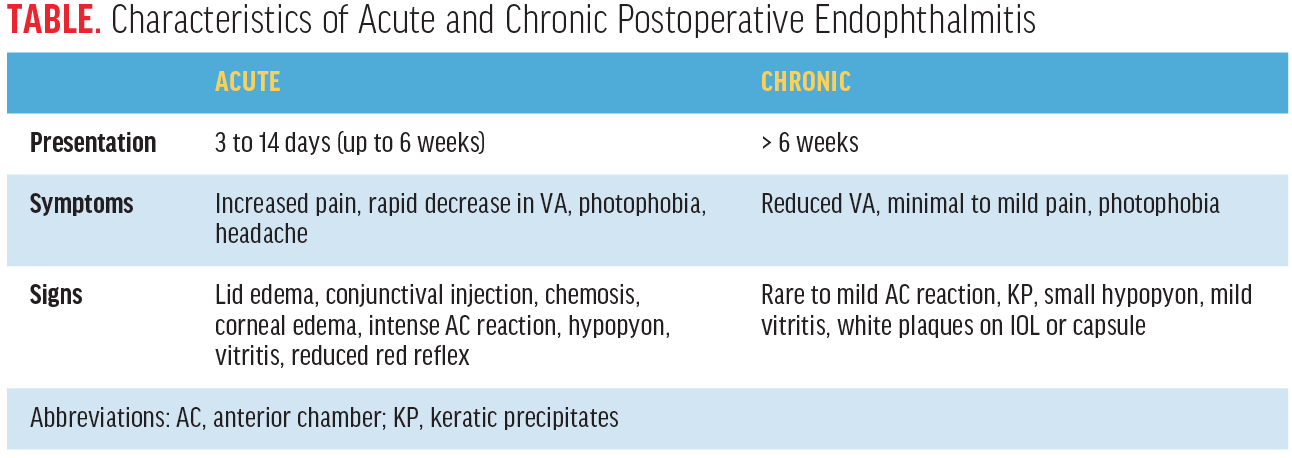

Postoperative endophthalmitis can present in either an early or acute form within days of surgery or a chronic delayed form, evidenced by more subtle symptoms several weeks after surgery (Table).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND MANAGEMENT

Acute postoperative endophthalmitis comprises 88% of all cases and typically manifests within 3 to 14 days after surgery.3 Patients will present with a progressive increase in pain, decreased VA, eyelid edema, conjunctival injection, and chemosis. They often report a significant, sudden reduction in VA, aching pain, and severe photophobia.1

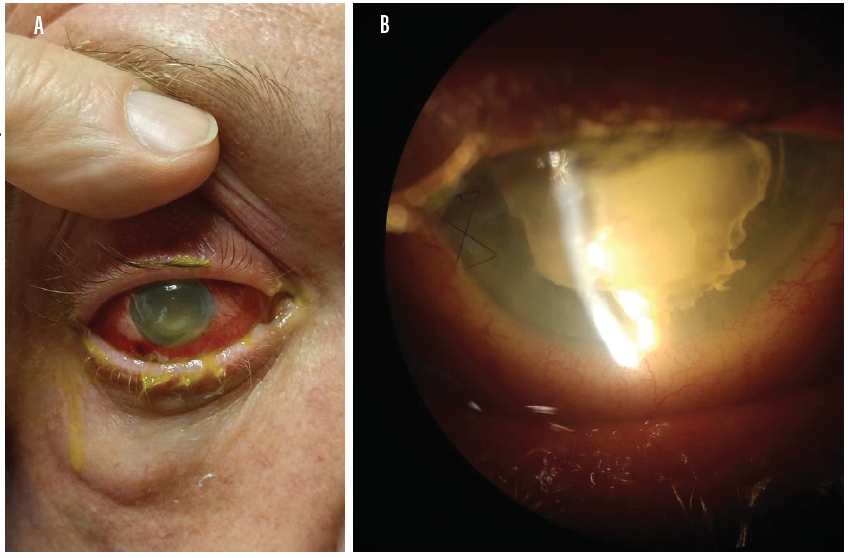

Clinical findings are easily noted on examination and can include intense anterior chamber reaction with significant cells and flare (Figure). Often, the severe inflammation is accompanied by fibrin and hypopyon. Vitreous cells are also present, and more severe infections can include loss of the red reflex and a VA of less than hand motions.1

Figure. Photos show a patient with acute endophthalmitis with significant conjunctival injection (A) and intense anterior chamber reaction with hypopyon and fibrin (B). (Photos courtesy of Jordan Heffez, MD.)

Chronic or delayed-onset endophthalmitis is less common, and symptoms may include only a mild, progressive deterioration of VA. This disorder can cause only mild pain and photophobia or can occur without those symptoms entirely. Clinical examination may reveal mild or rare cell reaction in the anterior chamber and vitreous. White plaques may be apparent on the IOL or capsule, and there may be evidence of keratic precipitates or small hypopyon.

When examining a patient, other diagnoses to consider in the differential include retained lens material, posterior segment syndromes, and sterile (noninfectious) intraocular inflammations such as toxic anterior segment syndrome.4

Acute postoperative endophthalmitis is a medical emergency and requires prompt attention. In all cases in which an OD is providing postoperative care, the operating surgeon should be contacted immediately and notified of the situation. Given the time-sensitive nature of the condition, arrangements should also be made for an urgent consultation with a retina specialist for timely initiation of therapy.

TREATMENT

Treatment for acute postoperative endophthalmitis follows the protocol determined by the Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study5 and consists of either vitrectomy or vitreous tap and intravitreal injection of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Intravitreal steroid therapy may be included to reduce inflammation, and topical antibiotics, steroids, and cycloplegics will be added to the regimen.

The treatment of delayed postoperative endophthalmitis includes aqueous cultures and polymerase chain reaction examination to help isolate the responsible organism. A combination of vitrectomy with intravitreal or intracameral antibiotics can be an acceptable treatment option. In persistent cases, explantation of the IOL and capsule may be indicated to completely eliminate the infection.1

PREVENTION

Given the significant and severe visual consequences of this condition, attention and discussion have focused on prophylaxis. The European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons published prospective study results in 2007 that demonstrated a five-fold reduction in postoperative endophthalmitis rates using intracameral cefuroxime.6-8 In addition, a retrospective study performed by surgeons with Kaiser Permanente reported a 22-fold reduction in postoperative endophthalmitis over 5 years with the routine use of intracameral antibiotics.6

Responses to the 2014 American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery members survey indicated increased adoption of intracameral antibiotic prophylaxis by US surgeons6 compared with responses to the same survey in 2007. Further, two-thirds of 2014 respondents reported that they believed intracameral antibiotic treatment was a very important option for the cataract surgeon to have, and more than 75% of respondents stated that it was important to have an approved and commercially formulated preparation widely available for use.6

BE READY TO RECOGNIZE AND ACT QUICKLY

As the volume of cataract surgeries increases to meet the demand of an aging population, surgeons will spend more time on preoperative consultation and in the OR, leaving ODs to perform the bulk of the postoperative care. With this in mind, we must consider endophthalmitis as a potential cause of any patient complaints of increasing pain or decreasing VA after surgery and act swiftly to minimize or avert the significant visual sequelae that can result.

1. Packer M, Chang D, Dewey S; ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee. Prevention, diagnosis, and management of acute postoperative bacterial endophthalmitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(9):1699-1714.

2. Buzard K, Liapis S. Prevention of endophthalmitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(9):1953-1959.

3. Hughes DS, Hill RJ. Infectious endophthalmitis after cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78(3):227-232.

4. Mamalis N, Edelhauser HF, Dawson DG, Chew J, LeBoyer RM, Werner L. Toxic anterior segment syndrome. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(2):324-333.

5. Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS). Clinicaltrials.gov. clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00000130. Updated September 17, 2009. Accessed October 1, 2019.

6. Chang D, Braga-Mele R, Henderson BA; ASCRS Cataract Clinical Committee. Antibiotic prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: results of the 2014 ASCRS member survey. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41:1300-1305.

7. Barry P, Seal DV, Gettinby G, Lees F, Peterson M, Revie CW; ESCRS Endophthalmitis Study Group. ESCRS study of prophylaxis of postoperative endophthalmitis after cataract surgery: preliminary report of principal results from a European multicenter study. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(3):407-410.

8. [no authors listed]. Endophthalmitis Study Group, European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(6):978-988.