With a growing population in need of cataract surgery, optometry’s role in managing patients with cataracts extends far beyond simply telling them they have cataracts and referring them to an ophthalmologist colleague. Optometrists should be prepared to discuss IOL implant options, address ocular and systemic health, and they should be comfortable managing or triaging any postoperative complication associated with cataract extraction.

Through advances in surgical techniques and technologies, cataract extraction has evolved from intracapsular to extracapsular cataract extraction to phacoemulsification and now laser cataract surgery. In modern cataract surgery, a small 1.0-mm sideport incision is made, OVDs are injected to maintain space in the eye and to protect ocular structures, a 2.0-mm to 3.0-mm clear corneal incision is made for the insertion of instruments, a capsulorhexis is made, the lens is removed using phacoemulsification, and an IOL is implanted.1

Although surgical techniques can vary, understanding the basics of the surgical procedure allows ODs to better address complications associated with cataract surgery, including inflammation, refractive status, elevated or decreased IOP, infection, and posterior capsular opacification. Postoperative complications of cataract surgery have been well documented, and every optometrist should be prepared to manage these complications within his or her scope of practice.

In this article, I focus on managing a patient’s IOP after cataract surgery.

ELEVATED IOP

Elevated IOP is one of the most frequent complications after cataract surgery.2 It occurs secondary to a combination of preexisting and iatrogenic components, which can include compromised outflow, retained OVD, surgical trauma, watertight wound closure, retained lenticular debris, release of iris pigment, hyphema, and inflammation.2

Retained OVD is thought to be a major contributor. After cataract extraction, any remaining OVD in either the lens capsule or the anterior chamber may obstruct trabecular outflow, resulting in elevated IOP.3 The elevation in IOP typically peaks at 3 to 7 hours after cataract extraction, persists for the first 24 hours, and returns to nearly normal levels within 48 hours.4-6 Numerous studies have documented this rise in IOP after cataract surgery, and it can be as high as 40 mm Hg in some cases.5

Although this transient rise in IOP is benign in most cases, for some patients it has the potential to threaten vision. Transient postoperative IOP elevation has been reported to cause optic atrophy, anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, and vascular events such as retinal vein occlusion.5 This elevated IOP also puts patients with optic nerves already compromised by glaucoma at risk of progression.5

Management Tactics

The Prophylactic Approach

There is no standard regimen to prophylactically address elevated postoperative IOP. Several studies have explored the use of intracameral, topical, and systemic hypotensive agents as prophylaxis for postoperative IOP elevation.5,7-9 However, these studies have produced conflicting results, and so there is no consensus on the efficacy of medical prophylaxis for IOP elevation. In most cases, IOP elevation was reduced but not totally eliminated, and in other cases the elevation in IOP was only delayed.3,5

Rainer et al compared the effect of topical dorzolamide HCl ophthalmic solution 2% (Trusopt, Merck), a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, with that of latanoprost ophthalmic solution 0.005% (Xalatan, Pfizer), a prostaglandin.10 Both drugs produced a clinically significant reduction in IOP at 6 hours; however, only dorzolamide was effective at 24 hours. Rainer et al also compared dorzolamide HCl 2%/timolol maleate sterile ophthalmic solution 0.5% (Cosopt PF, Akorn) with latanoprost alone and found that the combination drug reduced IOP more effectively than latanoprost. However, in Rainer’s comparison, only dorzolamide-timolol prevented IOP spikes of greater than 30 mm Hg.10 The literature shows no consensus regarding prophylactic treatment of IOP after cataract surgery; this makes the day 1 postoperative IOP check important, as pressures can be unpredictable.

Clinically, IOP at or near 30 mm Hg in a healthy eye can be treated topically. The administration of one drop of a fixed-combination hypotensive, such as dorzolamide-timolol, will effectively reduce the pressure to an acceptable level (below 28 mm Hg). Once IOP reaches an acceptable level, the patient can be released without the need to remain on the hypotensive medication at home. In the event that IOP is elevated to 30 mm Hg to 40 mm Hg, some clinicians will recommend the addition of oral acetazolamide in conjunction with topical hypotensive therapy to bring the IOP to an acceptable level.

Sideport Paracentesis

The rationale behind sideport paracentesis is to provide an immediate reduction in IOP. To perform sideport paracentesis, pressure is applied to the edge of an existing sideport incision using a sterile instrument to release aqueous humor, which will appear as a positive Seidel sign with the use of fluorescein. This method has been shown to produce an immediate reduction in IOP; however, the pressure then returns to elevated levels within 4 hours.11 It is recommended that topical and/or oral hypotensives be administered to a patient undergoing paracentesis in order to promote a sustained reduction in IOP.5,11 In eyes with a high risk for optic nerve damage, a similar medical approach should be taken to address elevated IOP.

Care should be taken to ensure that the IOP is adequately controlled for the individual patient. Follow-up should be driven by the nature of the case. For glaucomatous patients, if IOP is elevated at day 1, they can be seen at a short interval to recheck pressure. Patients not considered to be at high risk can be seen 1 to 2 weeks postoperatively, depending on the provider’s preferred follow-up schedule.

It is important to remember at the 24-hour postoperative examination that, if the pressure is elevated, it is likely not a steroid response. Elevated IOP secondary to a steroid response typically happens 10 days to 2 weeks after steroid treatment is initiated. If a patient’s IOP is elevated at this time, the best treatment is to taper or stop the steroid and switch to a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug to control the inflammation. In some cases, the addition of a topical hypotensive may be beneficial.12

LOWER-THAN-EXPECTED IOP

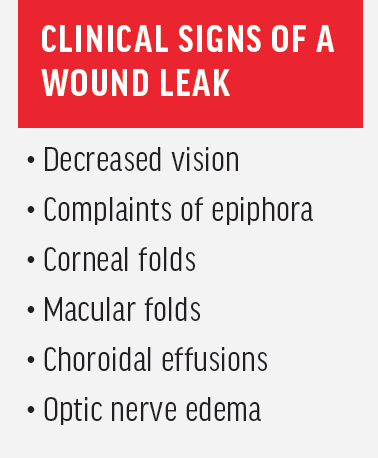

IOP can also be lower than expected 1 day after cataract surgery. During surgery, many surgeons fashion a clear corneal incision with three-plane, self-sealing architecture to reduce the need for sutures.13 With this incision design, there is a risk for wound leaks (see Clinical Signs of a Wound Leak). Patients at increased risk for wound leaks include those who underwent complicated cataract surgeries with prolonged surgical time and those who had mature cataracts, zonular dehiscence, or zonular laxity.13 Additionally, patients with a history of vitrectomy or LASIK, especially hyperopic LASIK, are at increased risk for wound leaks.13

Patients exhibiting a wound leak are at increased risk of hypotony, infection, and IOL instability, which may be of concern in patients with a toric IOL because rotation can significantly degrade VA.13 If a patient’s IOP is below 10 mm Hg in the 24 hours after surgery, evaluation for the presence of a Seidel sign is warranted. During examination, the rate of the Seidel should be noted, as should the depth of the anterior chamber.

Management Tactics

A wound leak that is mild will usually self-seal within 1 to 2 days. For leaks that are moderate in an eye with a formed anterior chamber, a bandage contact lens can be placed to reduce lid interaction and promote epithelialization. When a bandage contact lens is introduced, the provider should increase the antibiotic frequency to at least six times a day.13,14 Some providers recommend decreasing the steroid and increasing the antibiotic to promote healing.

Patients should be seen every 1 to 2 days until the leak is resolved. Patients should be educated on continued use of a shield while sleeping and should be told to avoid rubbing their eyes and getting water directly into their eyes. Warning signs of infection should be reviewed as well. If the leak is not resolving, the IOP is consistently low, or the anterior chamber is shallow or flat, the patient should be referred back to the surgeon for consultation and possible surgical repair or revision.13,14

RISE TO THE OCCASION

As the number of patients undergoing cataract surgery continues to rise, it is more important than ever for optometrists to be prepared to address any perioperative needs that arise. Elevated IOP and decreased IOP with wound leaks are postoperative complications that every optometrist comanaging cataract patients should be equipped to handle.

1. Davis G. The evolution of cataract surgery. Mo Med. 2016;113(1):58-62.

2. Gokhale P, Patterson E. Elevated IOP after cataract surgery. Cataract & Refractive Surgery Today. 2008;8(7):1-9.

3. Grzybowski A, Kanclerz P. Early postoperative intraocular pressure elevation following cataract surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2019;30(1):56-62.

4. Kim JY, Jo MW, Brauner SC, et al. Increased intraocular pressure on the first postoperative day following resident-performed cataract surgery. Eye (Lond). 2011;25(7):929-936.

5. Ahmed II, Kranenmann C, Chipman M, Malam F. Revisiting early postoperative follow-up after phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28(1):100-108.

6. Henry JC, Olander K. Comparison of the effect of four viscoelastic agents on early postoperative intraocular pressure. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1996;22(7):960-966.

7. Dayanir V, Ozcura F, Kir E, et al. Medical control of intraocular pressure after phacoemulsification. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:484-488.

8. Fry LL. Comparison of the postoperative intraocular pressure with Betagan, Betoptic, Timoptic, Iopidine, Diamox, Pilopine Gel and Miostat. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1992;18:14-19.

9. Bomer TG, Lagreze W, Funk J. Intraocular pressure rise after phacoemulsification with posterior chamber lens implantation: effect of prophylactic medication, wound closure and surgeon’s experience. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:809-813.

10. Rainer G, Menapace R, Findl O, Petternel V, Kiss B, Georgopoulos M. Intraindividual comparison of the effects of a fixed dorzolamide-timolol combination and latanoprost on intraocular pressure after small incision cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(5):706-710.

11. John M, Souchek J, Noblitt RL, et al. Sideport incision paracentesis versus antiglaucoma medication to control postoperative pressure rises after intraocular lens surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19(1):62-63.

12. Devgan U. Managing IOP issues after cataract surgery. Ocular Surgery News. January 25, 2015. www.healio.com/ophthalmology/cataract-surgery/news/print/ocular-surgery-news/%7Bfc3ec201-bf2c-4b06-ae03-53acb8dbff2c%7D/managing-iop-issues-after-cataract-surgery. Accessed September 16, 2019.

13. Matossian C, Makari S, Potvin R. Cataract surgery and methods of wound closure: a review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:921-928.

14. Cunningham DN, Whitley WO. How to handle wound leakage. Review of Optometry. May 15, 2013. www.reviewofoptometry.com/article/how-to-handle-wound-leakage. Accessed September 16, 2019.