The care of patients with diabetic eye disease is complex, involving a number of physicians and clinicians. Optometrists are often the first clinicians to detect diabetic eye disease in a patient, and in such case, they are obliged to educate the patient and also inform his or her care team of the diagnosis. Retina specialists are involved in the treatment of the chronic manifestations of diabetic eye disease, which benefits from good patient adherence and ongoing education.

AT A GLANCE

- Optometrists and ophthalmologists both have vital roles to play in the care of patients with diabetic eye disease.

- As primary eye care providers, optometrists are often the first to detect diabetic eye disease, in which case patient education is crucial.

- Retina specialists can use imaging as a tool to further educate patients referred for treatment.

In this article, we separately review the roles of optometrist and specialty ophthalmologist on the management team of patients with diabetic eye disease.

Optometrists as Educators and Communicators

By Sherrol Reynolds, OD, FAAO

Optometrists play a vital role in educating patients with diabetes about their disease and how best to manage it to prevent or reduce progression of vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (DR) and diabetic macular edema (DME). It is also essential for optometrists to establish partnerships with the other health care providers involved in the care of their patients with diabetes and to maintain consistent communication with all of them. In this scenario, the optometrist serves as an educator for the patient and as the point person for the patient’s care team.

EDUCATOR

To reduce the risk or slow the progression of DR and DME, it is important to counsel patients on modifiable risk factors, the ABCS of diabetes:

- A: A1c (glycosylated hemoglobin) level

- B: blood pressure

- C: cholesterol

- S: smoking cessation

Good glycemic control (A1c ≤7), a healthy blood pressure level (≤130/80 mm Hg), and low cholesterol levels are all key to reducing or preventing the progression of complications of diabetes. Ask patients to report their most recent A1c levels. Use simple terms that they can understand, such as “your 3-month blood sugar.” Some patients will instead offer daily blood sugar test numbers. Talk to patients about the importance of smoking cessation and proper nutrition.

Provide educational information and brochures about DR and DME. When possible, these materials should be in the patient’s preferred language.

Educate patients about how outcomes have improved due to new technologies such as widefield imaging that can detect early DR changes. Inform them about the latest in management strategies, such as frequent monitoring with 3-month follow-up.

When you must refer patients to a retina specialist, inform them about the anti-VEGF and steroid therapies that have replaced laser treatment as the standard of care for many patients with diabetic eye disease. Patients may express fears and apprehension about eye injections; encourage them to ask questions and address any concerns. This will help to improve follow-up and compliance with care.

COMMUNICATOR

Treatment for a systemic disease such as diabetes requires a multidisciplinary team. It is incumbent upon optometrists who encounter patients with diabetic eye disease to coordinate communication with the patient’s care team, which often includes (or will eventually include) a primary care provider (PCP), an endocrinologist, and a retina specialist.

A yearly diabetic eye examination is essential, and all members of the patient’s diabetes health care team must consistently reinforce the importance of a regular dilated retinal examination.

PATIENT CASE

In some cases, the optometrist is the first clinician whom a patient has visited in a long time. A recent experience illustrates the value of serving as an educational point person.

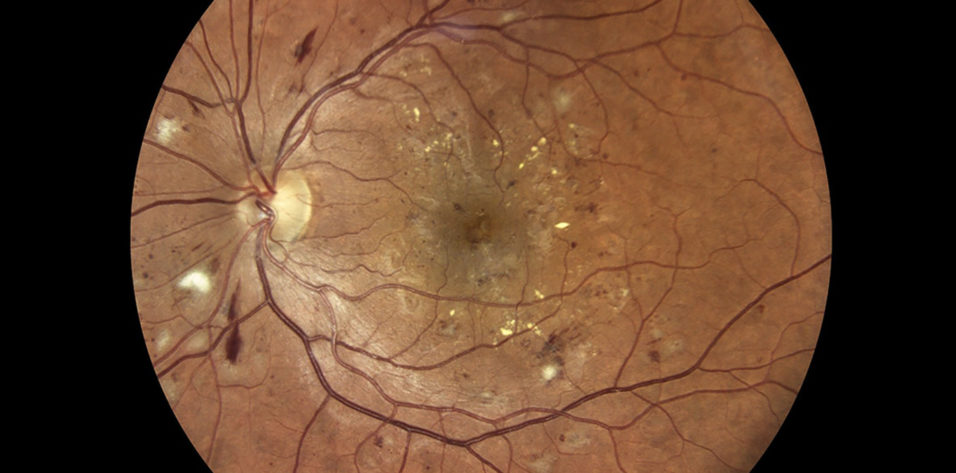

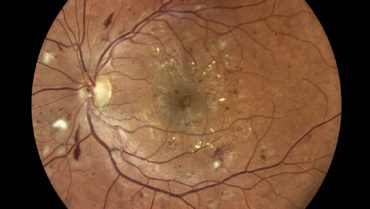

A patient presented to my office complaining of a visual disturbance. He reported a history of type 2 diabetes, but he informed me that he had “cured” his disease, stopped taking medication, and had not visited his PCP or any eye care professional in several years. Examination showed that he had nonproliferative DR with DME (Figure).

Figure. A patient who had not been seen by an eye care professional in several years presented with nonproliferative DR, as seen in this fundus image.

Photo courtesy of Nicole Harris, OD

This patient was educated about his disease, his risk of vision loss, and his need for a team of doctors to effectively manage his condition. My office immediately contacted the offices of the patient’s PCP and retina specialist to communicate our clinical findings and make appointments for the patient. Three-month follow-up was scheduled to ensure patient compliance with recommended care.

Imaging as an Educational Tool to Drive Compliance

By S.K. Steven Houston III, MD

Patients with DR may be lost to follow-up for any number of reasons, including those related to insurance, finances, comorbidities, and transportation. Patient education is key to mitigating the risk of losing these patients to follow-up, and imaging can play an important role in teaching patients about their disease and illustrating disease progression, regression, or stability. Here are three ways I use imaging to educate new and returning patients about their DR.

DETAILS AT DIAGNOSIS

For any patient who presents with DR, I acquire widefield imaging (optomap, Optos) and spectral-domain OCT (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering). These imaging tests allow me to make an accurate diagnosis in new patients and also provide tools I can use to educate these patients about their disease.

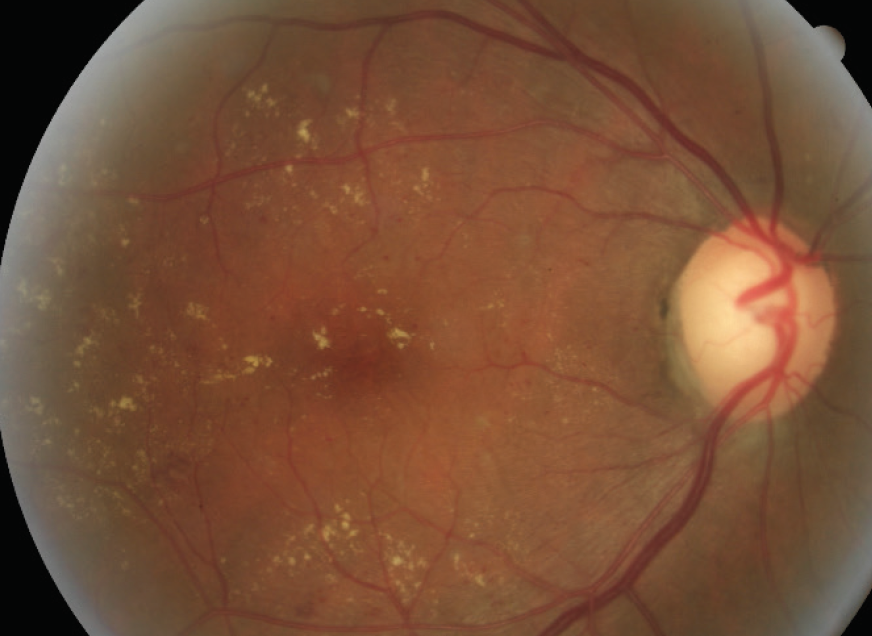

Patients who have not been educated about diabetes and its complications can see their hemorrhages on widefield imaging and their anatomic disruptions on OCT. These images allow me to show patients the severity of their disease. Comparing the imaging results of a patient with DR to those of a healthy patient can help the patient understand the risk of vision loss.

TRACKING PROGRESS

Patients undergoing treatment are often curious about their progress. Imaging results can be a useful way to show progression, regression, or stability of disease activity. This applies both to patients undergoing treatment and to those whose disease requires only monitoring.

Take, for example, a patient with DME whose disease requires monitoring because it has not met the threshold for therapeutic intervention. If that patient returns with 1 or 2 lines of visual acuity loss, imaging can help the patient link visual decline with anatomic changes. As that patient returns for treatment and his or her vision improves, imaging can illustrate the connection between therapy and that visual improvement. This connection may increase the likelihood that the patient will be compliant.

Interpretation of imaging results can be intuitive for patients. I often find patients looking at their OCT imaging results before I enter the exam room, and they can point to improvements or regressions in their anatomic results. For these patients, I know that the connection between therapy and disease status has been absorbed and learned.

DRIVING HOME COMPLIANCE FOR ASYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

Patients with DR often have other diabetic comorbidities. Microvascular complications that do not have readily apparent effects on the body (ie, nephropathy) can be difficult to conceptualize, whereas those with obvious manifestations (ie, diabetic neuropathy) are easier to understand. Vision loss related to DR or DME falls into the latter group.

Patients with DR who have no functional vision loss may better understand the pending threat to their vision if they can see diabetic vitreous hemorrhages or other anatomic complications that may not yet have interfered significantly with their vision. I show such patients imaging results so they can see that, without intervention or behavioral change, the hemorrhages or retinal thickness increases lurking around the corner may soon affect their vision.

KEEPING IT REAL

To sum up the specialist perspective, patient education is key in improving compliance in patients with DR and DME, and imaging can be a useful tool in that education. It can help patients connect occurrences in their eyes to the visual disruption they are experiencing. Patients returning for follow-up can track their disease progress via imaging. And asymptomatic patients may better understand their risk for vision loss if imaging results are used to illustrate the severity of anatomic disruption.

PULLING IT ALL TOGETHER

For many patients with diabetes, vision loss is the most feared complication. By educating patients on the complexities of their disease, reinforcing the need for team-based care, and communicating with other specialists involved in their care, optometrists can set the tone for patient care and start treatment off on the right foot.

Patient education, whether delivered by the optometrist or the retina specialist, is key to increasing the likelihood that patients comply with treatment recommendations. As clinicians charged with patient care, it falls upon both optometrists and ophthalmologists to participate in the education of patients whose diabetes has started to affect their vision.