I asked three vitreoretinal subspecialists to address diagnosis and treatment of three common posterior segment issues that may first be detected in the optometric setting.

DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA

Diabetes is an epidemic in the United States, affecting more than 30 million people. Many individuals with diabetes will develop some degree of retinopathy. Complications associated with diabetic retinopathy, such as diabetic macular edema (DME), are the leading causes of blindness among young US working adults. Hence, early detection and prompt management are crucial. I asked Gary Sheinbaum, MD, to discuss the examination and treatment of patients who may have DME.

Diana Shechtman, OD, FAAO: When we examine the fundus, when should we suspect DME?

Gary Sheinbaum, MD: Suspect DME when there are microaneurysms, hard exudates, hemorrhage, and/or thickening in the macula. Hard exudates in particular should prompt you to be suspicious of DME.

Dr. Shechtman: When should DME be treated? What is the distinction between center-involved and non–center-involved? Do you ever treat a 20/20 eye with DME?

Dr. Sheinbaum: Anti-VEGF agents are commonly employed for patients with center-involved DME. DME is also treated when it is deemed to be clinically significant macular edema (as characterized Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study criteria) or non–center-involved. I commonly implement focal laser if open microaneurysms are denoted.

Treating a 20/20 eye is controversial because neither the ETDRS nor more recent trials investigating the efficacy of intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy and steroids included 20/20 eyes. Many treat such patients based on findings, symptomatology, or associated ischemia, as denoted by fluorescein angiography. Currently, Protocol V of the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) is investigating the use of anti-VEGF therapy in the treatment of DME in patients with better than 20/25 visual acuity.

Dr. Shechtman: What are today’s treatment options, and when are they implemented? Is there still room for laser?

Dr. Sheinbaum: Today’s treatment options include focal laser, intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy, and intravitreal steroid therapy via triamcinolone intravitreal injection, the dexamethasone intravitreal implant 0.7 mg (»Ozurdex, Allergan), or the fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant 0.19 mg (»Iluvien, Alimera Sciences). My first-line treatment for center-involved DME is typically intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy. Because steroids can worsen cataracts and elevate IOP, they may be best suited for patients who do not initially respond well to anti-VEGF therapy or who are pseudophakic (or planning cataract surgery in the near future) and have no associated glaucoma complications. In my opinion there is still role for focal laser, particularly in the setting of clinically significant macular edema that does not involve the foveal center.

WET AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness in the elderly. During the past decade, anti-VEGF therapy has become one of the most effective treatment options for wet AMD. Early diagnosis of wet AMD is imperative, as choroidal neovascular membranes can grow rapidly if left untreated. Marco A. Gonzalez, MD, sat down with me to discuss examination, imaging, and treatment for AMD.

Dr. Shechtman: When should we suspect wet AMD?

Marco A. Gonzalez, MD: I suspect wet AMD on examination when there is thickening of the retina, the presence of large pigment epithelial detachments, and/or the presence of subretinal fluid. Given the propensity of dry AMD to distort the normal topographic configuration of the macula with numerous drusenoid deposits and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) changes, finding signs of exudation can sometimes be difficult without the aid of OCT. Additional clues such as hemorrhages or exudates are less likely present but more easily seen on funduscopic examination. Subretinal fibrosis, presenting as deep areas of white fibrotic material, may also provide clues to the chronicity of disease and the presence of past or current choroidal neovascularization (CNV). A patient with complaints of acute metamorphopsia or decreased vision should raise high suspicion, as this likely implies recent change in macular topography regardless of examination findings. These subtle symptoms may indicate conversion to wet AMD.

Dr. Shechtman: What signs on OCT should increase the suspicion of conversion to wet AMD?

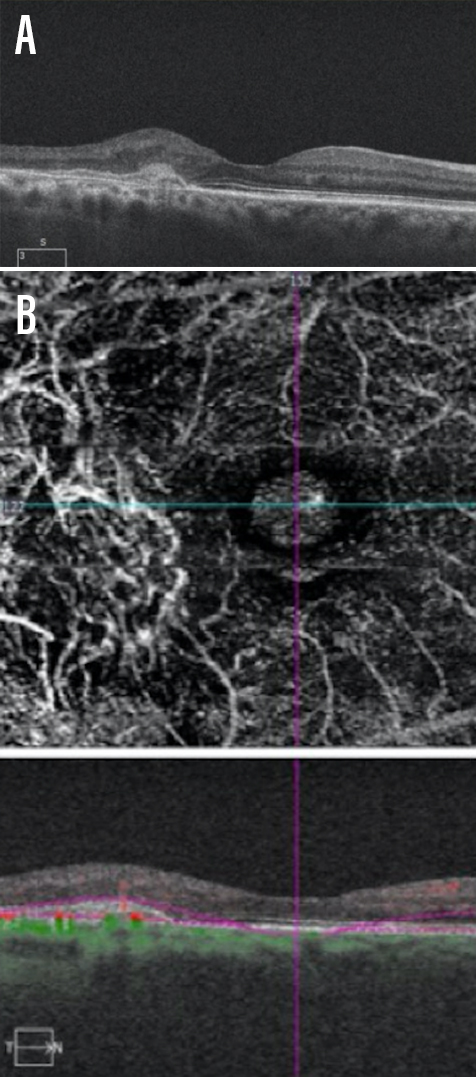

Dr. Gonzalez: Intraretinal and/or subretinal fluid implies the presence of exudation, and fluid is most commonly represented by hyporeflective areas within the retina or underneath it on OCT B-scans. Macular map thickening, although less specific, can also imply the presence of fluid, especially when compared with previous scans. Furthermore, hyperreflective subretinal lesions should raise suspicion for CNV and/or subretinal hemorrhage (Figure 1). Dynamically changing pigment epithelial detachments over time (especially over weeks) may point to the presence of a sub-RPE neovascular membrane. Finally, a long, irregular RPE elevation should raise suspicion for subclinical CNV.

Figure 1. A patient presented with age-related macular degeneration with evidence of a hyperreflective lesion in the subretinal space (A). The hyperreflective region corresponded with atypical vascular structure on OCT-A (B).

Dr. Shechtman: Is OCT standard of care for AMD evaluation and management?

Dr. Gonzalez: Given the difficulty of discerning subtle fluid on fundoscopic examination in the presence of baseline macular topographic changes, I would say that OCT is standard of care for initial evaluation of intermediate to advanced AMD. Further, OCT is often used to guide changes in treatment frequency, as it allows the clinician to objectively measure response to anti-VEGF therapy over time.

FLOATERS AND POSTERIOR VITREOUS DETACHMENT

The most common complaint encountered in retinal practice is floaters. Although causes may vary, the most common cause of floaters is posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). Primary management can include identifying and treating preexisting underlying conditions or simply observing. Unfortunately, observation does not always address the patient’s symptoms. Rashid M. Taher, MD, joined me for a conversation on floaters and PVD.

Dr. Shechtman: When should I worry about a PVD?

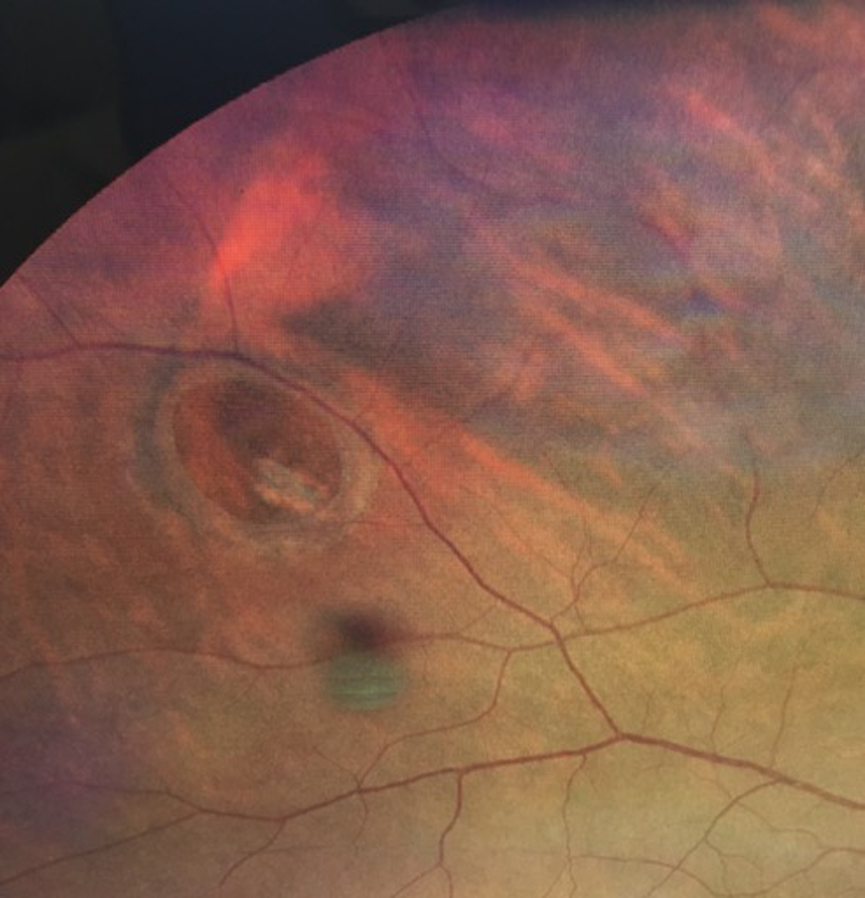

Rashid M. Taher, MD: Referral to retina subspecialist should be at the discretion of the OD. However, there is an increased risk of concomitant retinal tear or detachment in the presence of acute symptomatic PVD (Figure 2). Thus, if any of the following are detected or suspected, emergent referral is warranted:

- pigment in the anterior vitreous, a.k.a. “tobacco dust” (occurs when pigment epithelial cells migrate through the tear and can be seen dispersed throughout the vitreous);

- retinal break (RB);

- vitreous bleed (increases the chance of concomitant RB by 50-70%);

- punctate intraretinal hemorrhages in the periphery (often indicates vitreous traction and may mark the site of a future tear);

- lattice degeneration with symptoms or associated break;

- retinal detachment;

- visible vitreoretinal traction.

Figure 2. A patient presented with a retinal break. Acute symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment is one cause of retinal breaks.

Dr. Shechtman: What is the follow-up time for PVD, and should ODs be doing scleral depression?

Dr. Taher: According to American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines, patients with acute PVD should be asked to return for reexamination between 1 and 8 weeks (depending on clinical findings and symptoms). The chance of concomitant RB at the time of PVD diagnosis is 8% to 26%. If no RB is found in the initial exam, the chance of developing an RB on future exanimation is 2% to 5%. Thus, it would behoove us to reexamine patients at shorter intervals.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines suggest that patients with acute PVD should have an examination of the peripheral fundus using scleral depression. Thus, in my opinion, scleral depression should be performed in all patients with symptoms or signs of vitreous or retinal detachment, which includes evaluation of a PVD.

Dr. Shechtman: What is your experience with floaterectomy—pars plana vitrectomy for the treatment of floaters?

Dr. Taher: The majority of patients will opt for the tincture of time to mitigate their symptoms of vitreous floaters. However, a subset of patients will have persistent and symptomatic floaters that interfere with their activities of daily living.

I have found pars plana vitrectomy to be a viable option for selected patients with floaters, yielding favorable outcomes, high surgical success rates, and minimal associated complications. Patients I consider candidates for floaterectomy have symptoms for more than 3 months and have floaters that they perceive to significantly affect their quality of life. I often employ ultrasonography to objectively assess the state of the vitreous.

I treat any existing RB during the procedure. In order to delay cataract formation, I perform core vitrectomy with preservation of the anterior hyaloid face. By assessing surgical intervention on an individual basis, I can meet patient expectations while mitigating the risk of complications.