Patients using scleral lenses may present with unique complications that can leave a practitioner and patient overwhelmed. Some complications are more common than others, and here are three major complications that a proficient scleral lens fitter should be able to recognize and manage.

MIDDAY FOGGING

Midday fogging (MDF) occurs when there is accumulation of debris in the postlens tear film reservoir during scleral lens wear. It occurs in approximately 30% of patients.1,2 The hallmark symptom of MDF is hazy, blurry vision that is often described as a foggy. MDF requires removal and reapplication of the scleral lens, which is a challenge for many patients.

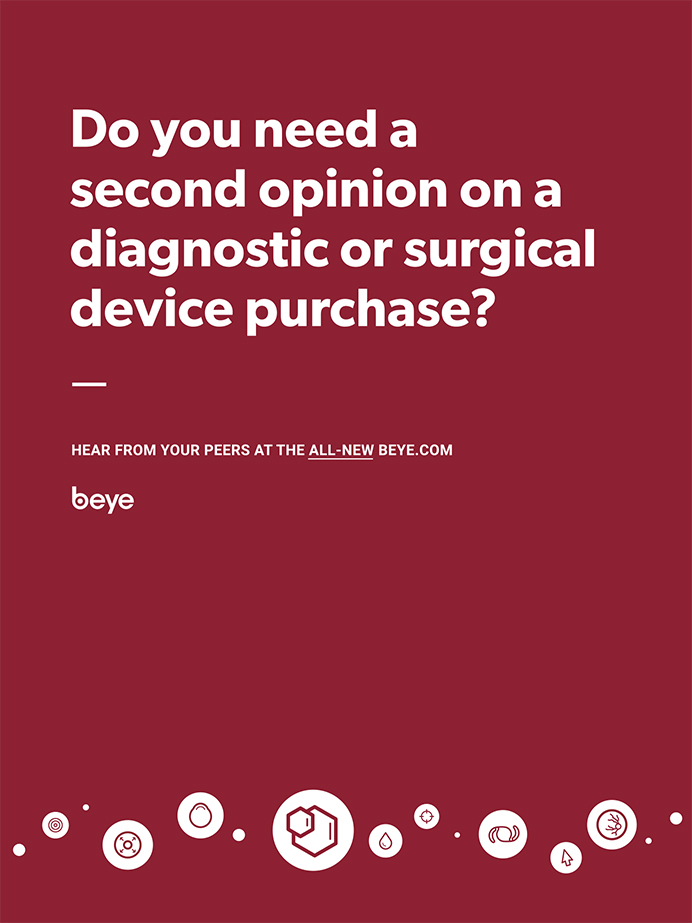

Debris in the tear film reservoir is visible on biomicroscopy (Figure 1). It should be noted that fogginess disappears immediately after scleral lens reapplication. If fogginess does not disappear, the possibility of lens nonwetting or corneal edema must be considered.

Figure 1. Midday fogging (indicated by yellow arrows) is visible on biomicroscopy as haziness over the pupil when viewed in full-field white light illumination (A). An optic section is used to localize the debris in the tear film reservoir (B). Debris is observable on OCT as hyperreflective debris in the tear film reservoir (C).

MDF management requires the clinician to adjust the lens fit by reducing overall sagittal depth and/or flattening the curve over the limbus (I suggest aiming for 50 µm clearance over the limbus). If the lens appears tight, flatten it or design a peripheral landing zone to reduce lens suction.

Allergies and dry eye disease, if present, should be treated. Improving eyelid health may help patients with meibomian gland dysfunction. Some patients may benefit from eyewash in the morning prior to scleral lens application. Patients may wish to change the application solution from saline to a high-viscosity, preservative-free artificial tear to help reduce debris accumulation.

SCLERAL MISALIGNMENT

Scleral misalignment occurs during uneven bearing on a scleral lens landing zone. Some cases are obvious; others are not.

The sclera is not spherical,3 and neither is the form-assuming conjunctiva that overlies it. Therefore, lenses with only one or two curvatures will not always sit flush on the ocular surface. Patients with scleral misalignment demonstrate increasing lens discomfort throughout the day. Patients may describe a mild headache or noticeable feeling after several hours of wear. There may be accompanying redness in the area of greatest bearing.

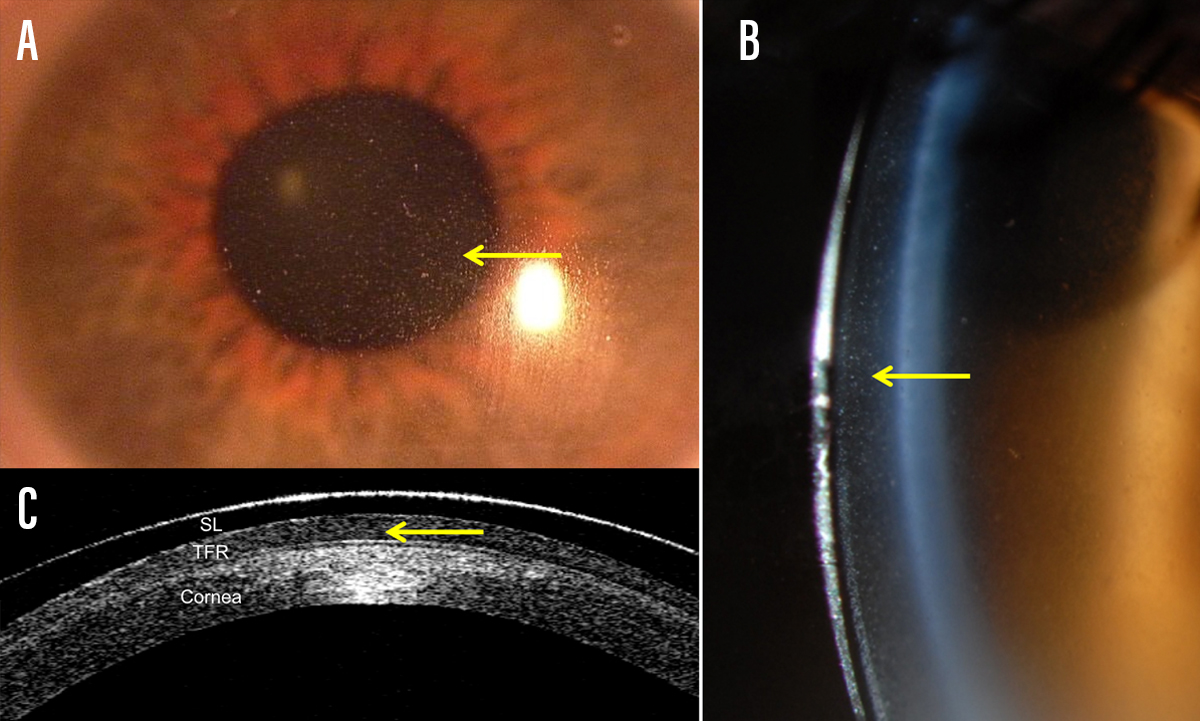

Major misalignment can be observed as impingement or bearing on the conjunctival blood vessels in one area of lens landing (Figure 2). Sometimes impingement is subtle, and a high-resolution OCT image may be needed to properly diagnose the condition.

Figure 2. Scleral lens impingement of a major conjunctival blood vessel is sometimes obvious on observation (A). Mild blanching can be more challenging to detect and may benefit from OCT imaging to determine if a lens is bearing down due to scleral misalignment (B).

Moving the scleral lens in real time to look at landing zone impingement may be helpful to tease out the areas of most compression. When OCT is unavailable, use of fluorescein sodium drops before removal can be useful if the clinician observes dye movement under the lens. Areas of greatest bearing will allow the least amount of fluorescein sodium into the tear chamber.

Changing the diameter of the scleral lens to find a landing zone (or what some call a haptic) that is more suitable for the patient’s anatomy will help fix scleral misalignment. You may need to try a few different designs and diameters to find the best fit for a highly asymmetric sclera; scleral topographers such as the sMap3D (Visionary Optics), the Eye Surface Profiler (Eaglet Eye) and tomographers such as the Pentacam (Oculus) are useful tools for measuring the sclera in these cases.4 You also may need to design a toric haptic,5,6 or find a quadrant-specific or molded haptic design that sits comfortably on the ocular surface.

CONJUNCTIVAL PROLAPSE

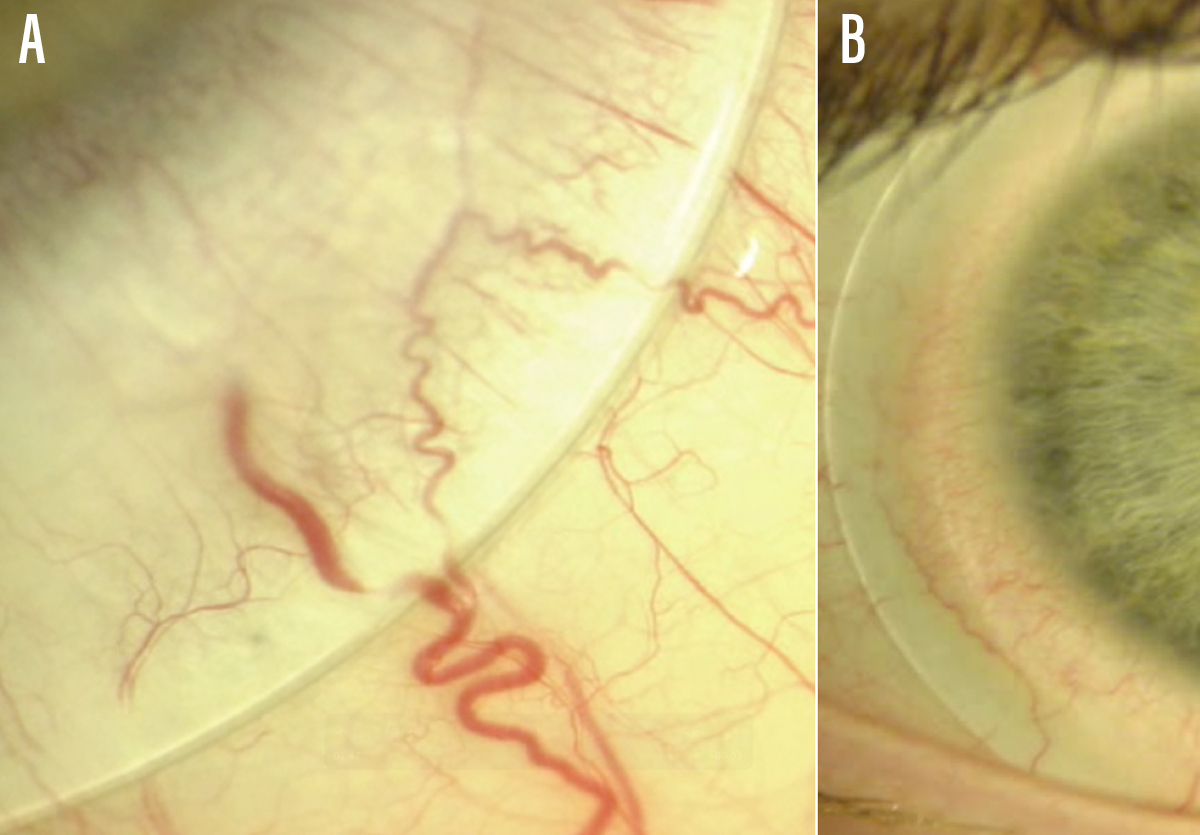

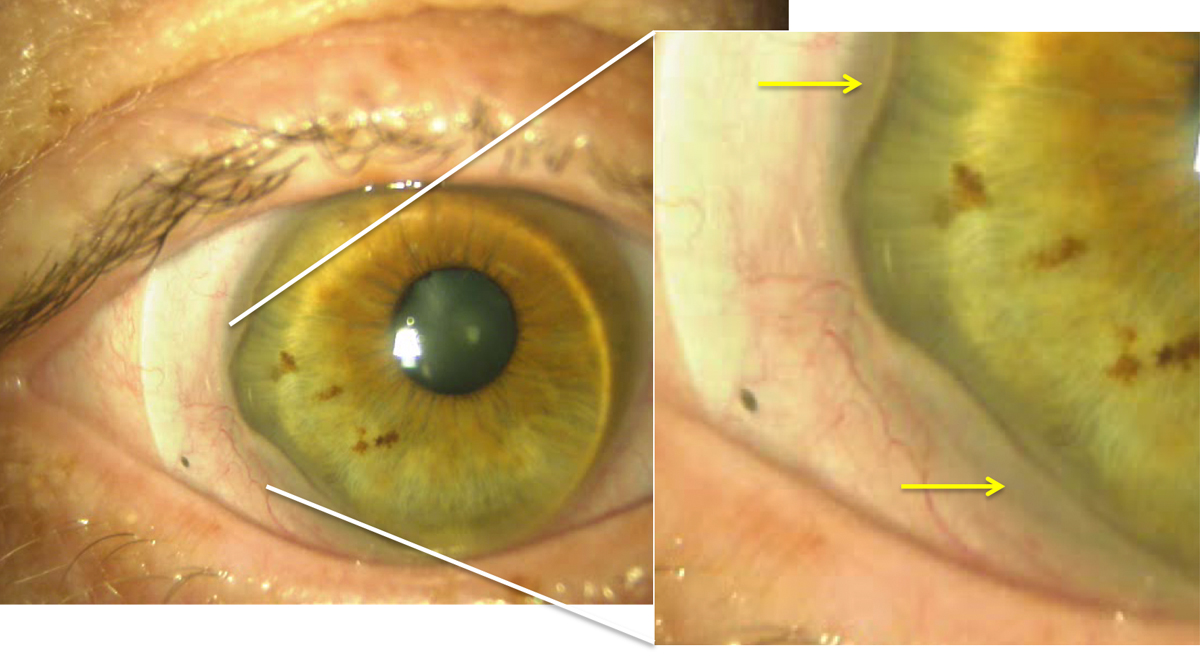

Patients with conjunctival prolapse may be asymptomatic; others may notice pink tissue at the boundary of the iris. Prolapse occurs when loose perilimbal conjunctival tissue is pulled between the scleral lens and the corneal limbus, often adhering to the corneal epithelium (Figure 3). It usually occurs in an inferior quadrant in the area where the lens is the greatest distance from the cornea (ie, area of the deepest tear reservoir thickness).7

Figure 3. Conjunctival prolapse (yellow arrows) is seen temporally and inferior temporally in this patient. The lens is decentered inferior temporally, which increases risk of developing prolapse in that area.

Conjunctival prolapse is simple to detect and diagnose, and the implications are unknown. A prolapse positioned over the corneal limbus could reduce the nutrients available to this part of the cornea. Corneal prolapse has not been shown to be associated with any long-term complications, but should be avoided as much as possible.

To address prolapse, a clinician should reduce the diameter of the lens to better center it and reduce susceptible areas to prolapse, and flatten the limbal curves to reduce excessive limbal clearance (I suggest aiming for ≤ 100 µm of limbal clearance).

KNOWING YOUR COMPLICATIONS

Scleral lenses are being fitted with increasing frequency, and the importance of proper management of the devices is essential. One key to a happy patient is proper diagnosis of sequelae unique to scleral lens usage. Methodical and informed observation and questioning will help scleral lens fitters become experts in managing these complications.

- Caroline P, Andre M. Cloudy vision with sclerals. Contact Lens Spectrum. 2012;27:56.

- McKinney A, Miller W, Leach N, et al. The cause of midday visual fogging in scleral gas permeable lens wearers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(15):5483

- Ritzmann M, Caroline PJ, Börret R, Korszen E. An analysis of anterior scleral shape and its role in the design and fitting of scleral contact lenses. Contact Lens Anterior Eye. 2018;41(2):205-213.

- van der Worp E, Bornman D, Ferreira DL, et al. Modern scleral contact lenses: a review. Contact Lens Anterior Eye. 2014;37(4):240-250.

- Visser ES, Visser R, Van Lier HJ. Advantages of toric scleral lenses. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83(4):233-236.

- Visser ES, Visser R, van Lier HJ, Otten HM. Modern scleral lenses part II: patient satisfaction. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33(1):21-25.

- Walker M, Bergmanson JP, Marsack JD, et al. Complications and fitting challenges associated with scleral contact lenses: a review. Contact Lens Anterior Eye. 2016;39(2):88-96.