Evaluation and management of anatomically narrow angles has never been a hot topic in eye care. Although anatomically narrow angles may not be the talk of the town in glaucoma (that distinction goes to microinvasive glaucoma surgery), evaluation and management of anatomical narrow angles is an important topic due to the potential sequelae of angle closure: angle-closure glaucoma, acute pain, and the potential for vision loss.

EXAMINATION

Careful examination of the angle anatomy of all patients is important, as many patients with potentially occludable angles present without symptoms. Angle evaluation is often overlooked during a comprehensive eye examination: A recent study found that 1.5% patients referred for cataract surgery to a tertiary care center were found to have undetected narrow angles or angle closure.1

Risk Factors

Some patients are more likely than others to have anatomically narrow angles. A careful history may identify a patient at risk for angle closure. Patients who are 60 or older, female, of Inuit or East Asian descent, hyperopic, or who have a family history of angle closure are more likely to develop angle closure than patients without these risk factors.2,3 Use of systemic medications such as topiramate, anticholinergics, and sympathomimetics may also increase risk of angle closure.

Dilation Ineffective

Dilating a patient with suspected narrow angle is a strategy some practitioners may use to identify angle closure in the office, but it should be noted that it is ineffective for this purpose. Angles usually close later in the period of dilation, when maximum contact between lens and iris tends to take place. Therefore, angle closure may occur 2 to 3 hours after the examination is over as the dilation wears off.3

Gonioscopy

Dynamic gonioscopy remains the gold standard methodology for evaluating a patient for angle closure. Use of a gonioscopic prism without flange during dynamic gonioscopy allows one to apply adequate but gentle pressure to decipher between peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) and iridotrabecular contact (ITC). With light pressure, an angle with ITC should open and angle structures should be more visible, whereas an angle with PAS will not move and the iris will remain over angle structures. Popular dynamic gonioscopy lenses include those manufactured by Zeiss and Volk, and Posner 4-mirror lenses. Gonioscopy should be performed in a dimly lit room with a narrow slit beam in order to minimize iris constriction.

The presence of PAS may hint that this angle closure is relatively chronic and the prognosis for IOP improvement if the angle is surgically opened. Both ITC and PAS can result in IOP spikes. ITC is much more likely than PAS to respond to treatments such as laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) or lens extraction. These therapies can help deepen the angle. However, they cannot peel the iris from the trabecular structures in the case of PAS.

Angles with significant PAS may require additional therapy to improve outflow, even if the iris structure can be brought away from the trabecular meshwork (TM). If the scleral spur can be identified, this means that the posterior TM, which is responsible for more of the aqueous outflow than the anterior TM,4 is available for draining. If no posterior TM is visible in two or more quadrants, the patient should be referred for further evaluation and possible treatment.3

Imaging

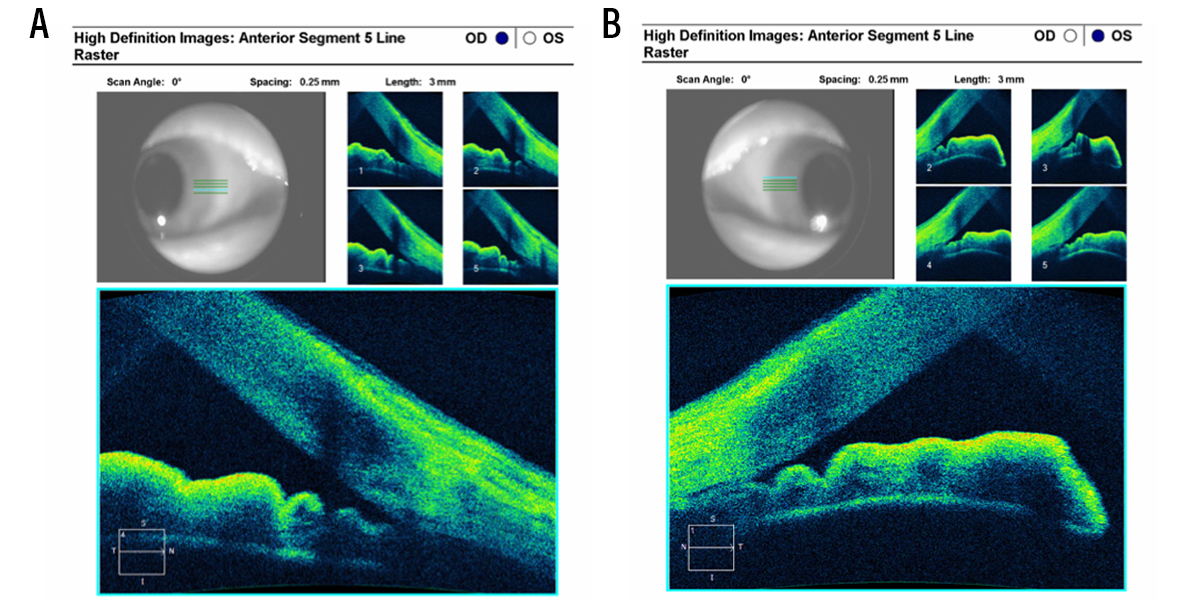

Anterior segment OCT and B-scan ultrasonography are useful for identifying a closed or narrow angle (Figure). Each can provide a view of the angle, and these imaging devices are useful if the clinician is not confident of the gonioscopic view. Anterior segment OCT can also be helpful for examination of patients who are uncooperative with gonioscopy or who have conditions that may contraindicate gonioscopy, such as a corneal erosion.

Figure. Anterior segment OCT image. A 68-year-old female with occludable narrow angles underwent cataract surgery in her right eye (A). Notice deepening of anterior chamber/opening of angle compared with her left eye, which had yet to undergo cataract extraction (B). Photo credit: Thomas Samuelson, MD.

TREATMENTS

Treatments for anatomically narrow angles are straightforward, and new evidence suggests that lens extraction may be more effective in some patients than LPI.

Laser Peripheral Iridotomy

Although LPI is a relatively straightforward procedure, it is not without risk. Glare, blurred vision, iritis, and hyphema are all associated with LPI.1,4,5

Concerns about superior versus nasal or temporal placement of LPI to avoid dysphotopsia may be for naught: A recent study that included 599 patients showed that LPI location did not predict risk of postoperative dysphotopsia.5 In the study, 8.9% of patients who underwent LPI reported at least one new symptom, the most common being glare (4.3%), blurring (4.3%), and linear dysphotopsia (2.7%). Patients with superior LPIs were not more likely to describe the new onset of one or more dysphotopsia symptoms than patients with nasal or temporal LPIs (8.4% vs. 9.5%; P = 0.7), nor did the frequency of any new individual symptoms differ by group (P < 0.3 for all). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, neither LPI location, nor LPI area, nor total laser energy predicted higher odds of new postoperative dysphotopsias (P < 0.1 for all).

Lens Extraction

Removal of the crystalline lens deepens the anterior chamber angle in angle closure suspects and patients with angle-closure glaucoma. An analysis of the effectiveness of early lens extraction for the treatment of primary angle-closure glaucoma, as measured by quality-of-life and cost-effectiveness calculations, showed that clear lens extraction was more efficacious and was more cost-effective than LPI.4

Patients with evidence of cataract and hyperopic patients could be candidates for lens extraction as a primary treatment of narrow angles. Presbyopic patients may also be good candidates, given improvements in presbyopia-correcting IOL technologies.

LPIs still have a place in treatment, but patients with narrow angles may benefit from a conversation about lens extraction as an option.4

OPENING OUR MINDS ABOUT NARROW ANGLES

Because patients with anatomically narrow angles are most likely to present without symptoms, with normal IOPs and healthy optic nerves, optometrists must be on alert to diagnose and potentially treat these patients before glaucomatous damage ensues.

- Varma DK, Kletke S, Rai AS, Ahmed IIK. Proportion of undetected narrow angles or angle closure in cataract surgery referrals. Can J Ophthalmol. 2017;52(4):366-372.

- Bowling B. Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systemic Approach. 8th ed. Sydney: 2016; Elsevier.

- Friedman DS. Epidemiology of angle-closure glaucoma. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2007;1(1):1-3.

- Azuara-Blanco A, Burr J, Ramsay C, et al; EAGLE Study Group. Effectiveness of early lens extraction for the treatment of primary angle-closure glaucoma (EAGLE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10052)1389-1397.

- Srinivasan K, Zebardast N, Krishnamurthy P, et al. Comparison of new visual disturbances after superior versus nasal/temporal laser peripheral iridotomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(3):345-351.