Eye care providers who encounter corneal conditions such as superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK), Salzmann nodular degeneration (SND), and ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) may wish to learn more about them. Here, I discuss those conditions in some detail.

SUPERIOR LIMBIC KERATOCONJUNCTIVITIS

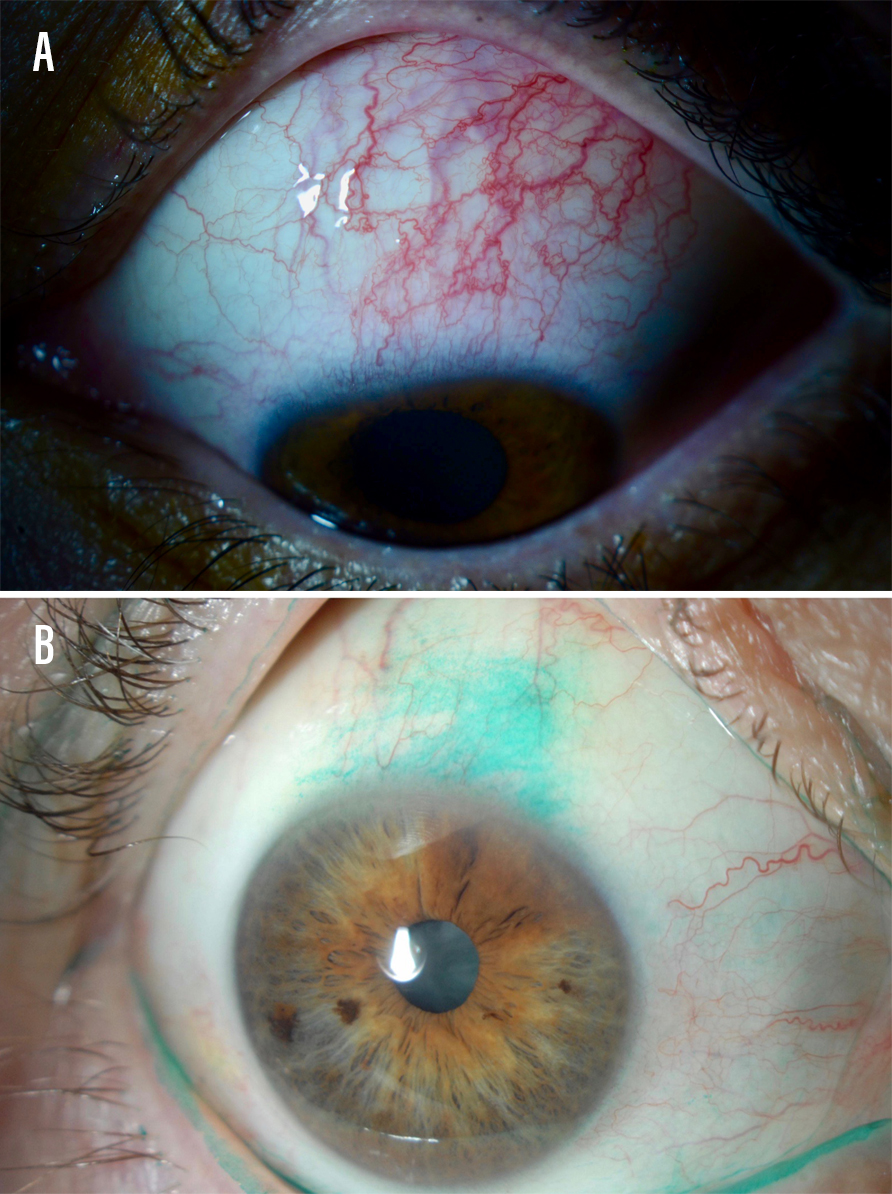

It is very important to look for SLK in patients with refractory dry eye disease symptoms. Unaddressed SLK is a frequent source of patient frustration: Patients have often seen clinician after clinician for what they think is dry eye disease that has not responded to treatment. This condition may be missed on examination if the superior conjunctiva and superior limbus are not examined by lifting the upper eyelid. During examination, the upper eyelid appears thickened with papillary hypertrophy of the tarsal surface, and the superior bulbar conjunctiva appears injected, excessively mobile, and stains with lissamine green (Figure 1). The superior cornea may exhibit superficial punctate keratitis and filaments.

Figure 1. A patient with superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis with inflamed superior bulbar conjunctiva (A). A patient with this condition who underwent lissamine green staining (B).

SLK may be associated with thyroid disease. Patients who present with this condition should be educated about risks and complications and sent for appropriate laboratory workups. The exact etiology of SLK is unknown. A popular working theory concerns mechanical friction between the tarsal conjunctiva and the superior bulbar conjunctiva and cornea.

Treatment options for SLK include topical lubricants, steroids, mast cell stabilizers, cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05% (»Restasis, Allergan), and large-diameter soft contact lenses. If a surgical solution is needed, I consider upper lid punctal plugs, silver nitrate solution, conjunctival cautery, or conjunctival resection.

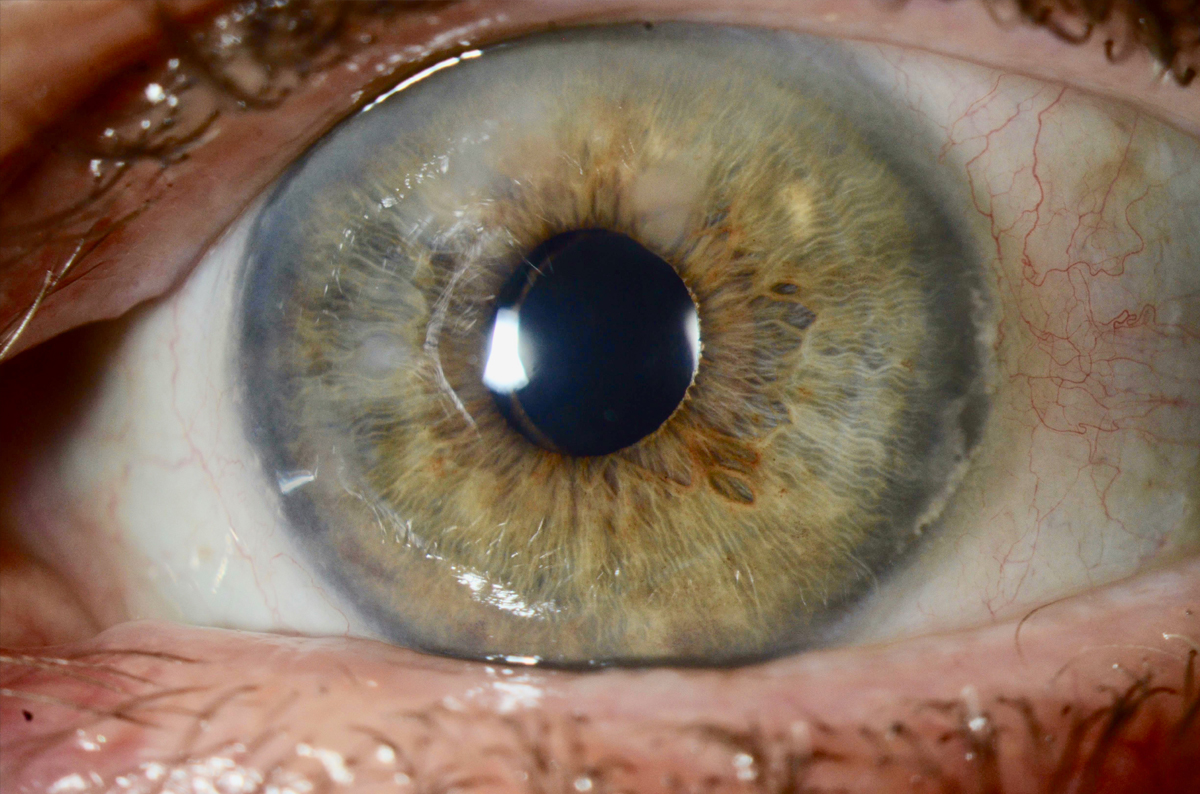

My go-to treatment is thermocauterization of the superior conjunctiva. It can be done in the office under local anesthesia and is tolerated fairly well. My technique involves ballooning the superior conjunctiva with an anesthetic such as lidocaine. I then use a handheld high-temperature unit to cauterize approximately 3 clock hours of superior conjunctiva. The marks on the conjunctiva usually fade in about 1 week, and patients generally report minor discomfort (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A case of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis immediately following thermocauterization treatment. Photo credit: Christopher Rapuano, MD.

SALZMANN NODULAR DEGENERATION

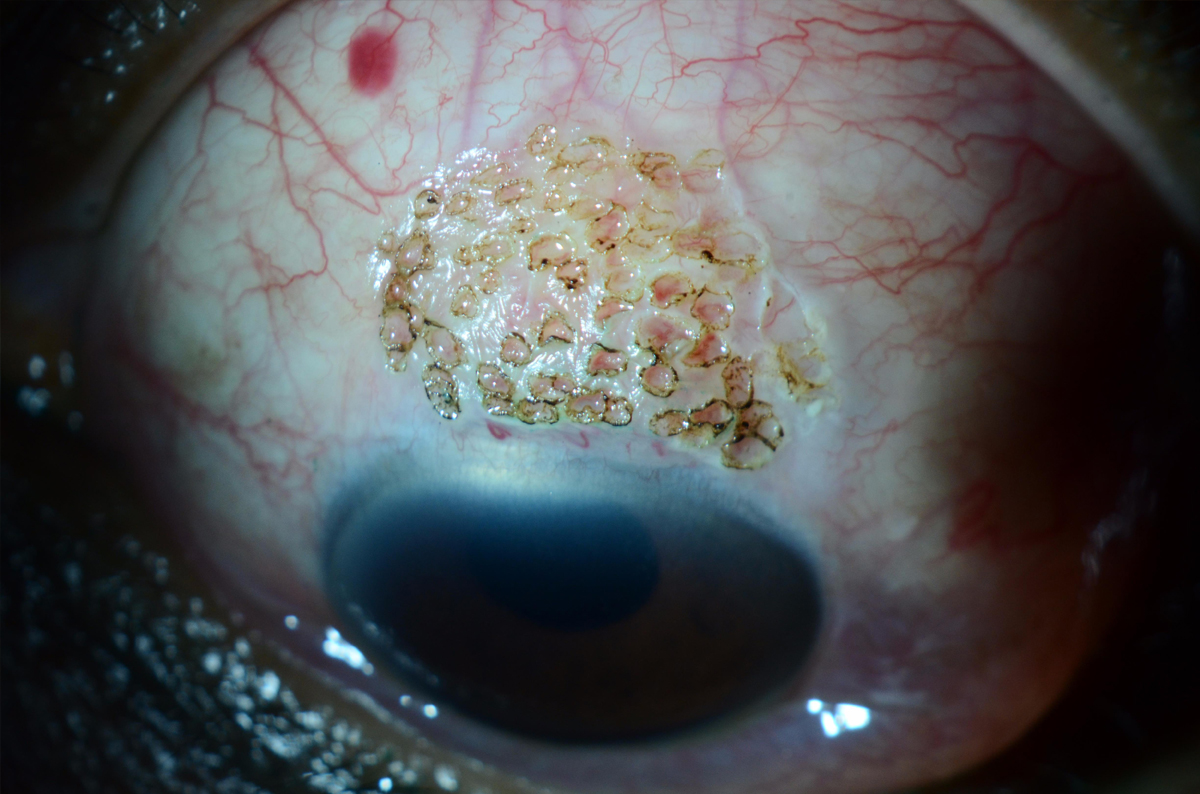

SND is a fairly common corneal disorder characterized by elevated gray-white lesions that are usually located in the peripheral or midperipheral cornea (Figure 3). They can be single or multifocal, unilateral or bilateral. Symptoms of SND include discomfort, foreign body sensation, and blurry vision induced by irregular astigmatism.

Figure 3. A patient with Salzmann nodular degeneration presents with elevated gray-white corneal lesions.

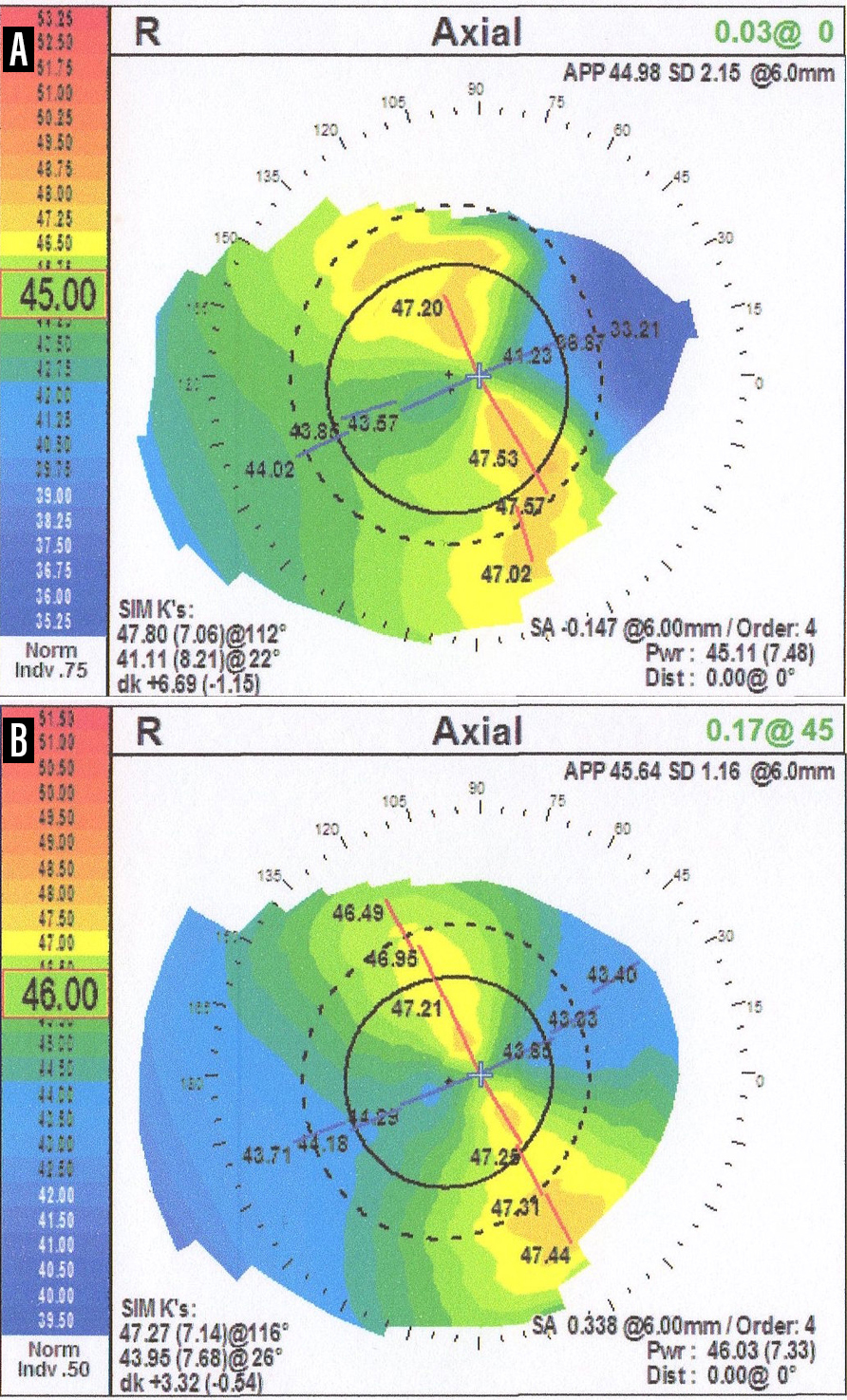

It is essential to diagnose SND during preoperative cataract surgery evaluations. SND may affect vision independent of the cataract and may alter corneal curvature, thereby causing IOL miscalculations. Patients who are considering astigmatism correction via IOL surgery should be particularly screened for SND.

Treatment for SND usually involves surgical excision, either manually or with excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy. After treatment, I typically allow the cornea to heal for approximately 2 months and then repeat IOL calculations before proceeding with cataract surgery. I often see a significant change in corneal astigmatism in the 2 months between treatment and preoperative IOL calculation (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Axial map topography of a patient with Salzmann nodular degeneration before treatment with superficial keratectomy (A). Two months after surgery, a change of 3.00 D in corneal astigmatism is observed (B).

OCULAR SURFACE SQUAMOUS NEOPLASIA

OSSN is used to describe a spectrum of conditions that affect both the cornea and conjunctiva. Because OSSN can range from corneal/conjunctival intraepithelial dysplasia to invasive squamous cell carcinoma, it is imperative that every clinician be on the look out for this condition and refer to the proper specialist for follow-up in a timely manner.

Patients with OSSN will present with lesions that commonly appear near the limbus in the interpalpebral area where the ocular surface is more exposed to UV light. It is especially important to keep OSSN in mind when you come across a patient with a lesion that resembles an atypical pterygium.

In cases of OSSN, a clinician will observe a corneal lesion that resembles a grey translucent epithelial sheet (Figure 5). The conjunctival portion of the lesion may vary in appearance, ranging between gelatinous, papilliform, or leukoplakic. Vital stains such as rose bengal and lissamine green can be helpful in both diagnosing and assessing the extent of disease, as the dysplastic epithelium in these lesions will stain.

Figure 5. A corneal and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia in a patient with ocular surface squamous neoplasia.

Treatment is generally complete excision using a no-touch technique with negative margins. An alcohol corneal epitheliectomy is used to remove corneal lesions. Double freeze-thaw cryotherapy is then applied to the margins and base of the resection zone. Topical chemotherapeutic agents such as mitomycin C, 5-flurouracil, or alpha-interferon 2B can be used as adjunctive therapy, either before or after surgery in cases of larger lesions. Additionally, in some cases I use these agents as primary therapy as an alternative to surgery with success.

BE ON THE LOOKOUT

It may be easy to overlook these corneal abnormalities during a routine examination. Still, clinicians examining patients with refractive dry eye disease, patients who are considering cataract surgery, or patients with an atypical pterygium should be on the lookout for these corneal pathologies.