Patients with diabetic eye disease may be scared to hear that their diabetes has affected their vision. Optometrists who identify diabetic eye disease in their offices are comfortable with referring these patients to a retina subspecialist; they may not be comfortable, however, answering all of their patients’ questions about ocular complications. In this article, I provide a quick run-down of pharmacologic and surgical innovations that have occurred in the past few years in the treatment of diabetic eye disease.

PHARMACOLOGY

Anti-VEGF Therapy

Arguably the most important innovation in the treatment of diabetic retinopathy (DR) and diabetic macular edema (DME) in the past decade-plus has been the introduction of anti-VEGF agents. Since early phase clinical trials,1 anti-VEGF agents have been shown not only to preserve visual acuity in patients with DME, but also to significantly improve vision in most patients. Three anti-VEGF agents can be used to treat DME: ranibizumab (»Lucentis, Genentech) and aflibercept (»Eylea, Regeneron) have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of DME, and bevacizumab (»Avastin, Genentech) has been used off-label to treat DME for a number of years.

The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network (DRCR.net) Protocol T study2 in patients with DME and baseline visual acuity of 20/50 or worse demonstrated that patients receiving ranibizumab or aflibercept treatment showed improved outcomes compared with those receiving bevacizumab. Still, it should be noted that all three agents offered significant visual and anatomic improvements over treatment with focal laser.

Recent studies have shown that anti-VEGF therapy can also reduce the occurrence of vision-threatening complications associated with proliferative DR (PDR).3 If untreated, PDR can cause vitreous hemorrhage and fibrovascular proliferation that can lead to tractional retinal detachment or neovascular glaucoma. The DRCR.net Protocol S study showed that ranibizumab treatment was comparable to panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) for treating PDR and was associated with a lower rate of vitrectomy. PDR can recur if anti-VEGF treatment is stopped. Thus, many retina specialists use anti-VEGF agents to control the short-term effects of PDR and use PRP to control its long-term effects.

Observation of patients being treated for DME in clinical trials showed that DR severity could be decreased with anti-VEGF treatment. The DRCR.net Protocol W study is investigating the use of anti-VEGF agents to prevent the worsening of DR, including progression from severe nonproliferative DR to PDR.4

Steroids

Just as patients respond differently to different anti-VEGF agents, so too do they respond differently to treatments that address different pharmacologic pathways. Patients whose diabetic eye disease is mediated by inflammation may respond to steroid therapy. The dexamethasone intravitreal implant (»Ozurdex, Allergan) and the fluocinolone acetonide intravitreal implant 0.19 mg (»Iluvien, Alimera Sciences) have both been approved by the FDA for treatment of diabetic eye disease. Many retina specialists initiate anti-VEGF or laser therapy before administering steroid therapy due to the complications associated with steroid use, including accelerated cataract formation and increases in intraocular pressure. For some patients, however, steroid therapy can be a type of reset button that calms inflammation and allows the patient to respond to other therapeutic pathways.

SURGICAL INNOVATIONS

Some patients with diabetic eye disease require surgical intervention. Small-gauge instrumentation, improved surgical techniques, and new tools for visualization have enhanced retina surgeons’ ability to perform surgery in diabetic patients.

Vitrectomy Tools

Modern surgical platforms allow surgeons to conduct minimally invasive surgery in an outpatient setting. These platforms use a range of small-gauge tools, which include vitrectors, forceps, lasers, picks, diathermy applicators, and scissors. The small-gauge instrumentation allows vitreoretinal surgeons to perform sutureless surgery with short recovery times.

A critical innovation in vitrectomy surgery was the introduction of valved trocars. Trocars placed in the sclera allow instruments to be easily exchanged throughout surgery. The valves prevent fluid egress and vitreous prolapse through the trocars and ensure a closed system. In surgery in diabetic patients, when bleeding can be a significant issue due to neovascularization, valved trocars create a state-of-the-art closed system to maintain hemostasis.

Bimanual Surgery

Diabetic tractional retinal detachments are challenging complications to address in surgery. Visualization is critical to satisfactorily segment and delaminate the preretinal fibrotic membranes causing traction on the retina.

Innovations in surgical equipment have helped usher in the era of bimanual retina surgery. In contrast with traditional vitrectomy (in which one hand manipulates a light pipe and the other the vitrector, laser, or forceps), bimanual maneuvers allow the surgeon to create countertraction with opposing instruments, such as with a lighted pick and forceps. Another option for bimanual surgery is a chandelier illuminator, inserted through a fourth trocar, placed either superiorly or inferiorly, to provide diffuse illumination.

Visualization

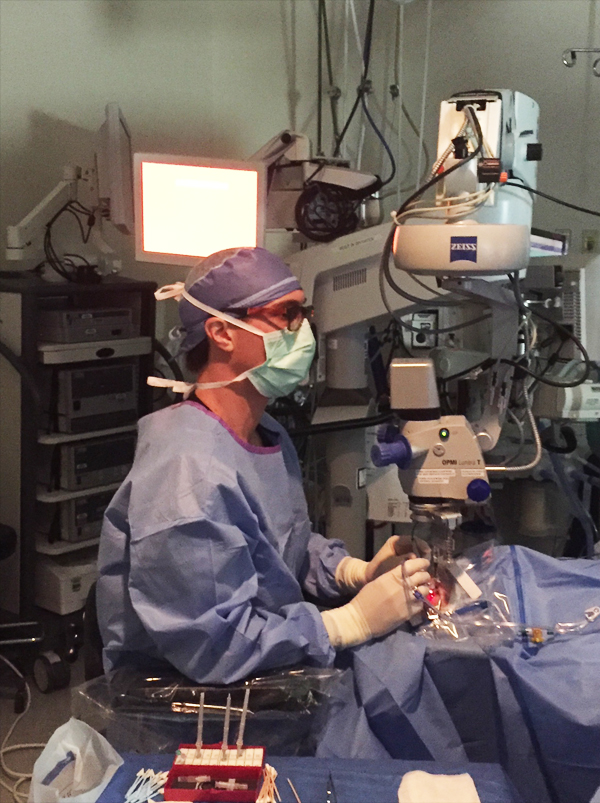

Recently introduced heads-up 3-D viewing systems have the potential to transform vitreoretinal surgery visualization. The Ngenuity 3D Visualization System (Alcon) employs an HDR camera system attached to the operating microscope; surgeons using Ngenuity no longer peer into the microscope during surgery, allowing them to keep the back straight during surgery. The surgeon operates wearing 3-D glasses and watching a 55-inch 3-D television (Figure).

Figure. Retina surgeons employing the Ngenuity vitrectomy platform can address ergonomic concerns, enhance depth of field, and improve overall visualization for the surgeon and all other OR staff (including technicians, residents, and fellows).

The system provides enhanced depth of field, maintains crisp focus, and increases magnification. The system also allows the surgeon to overlay critical clinical imaging (eg, fluorescein angiography, spectral-domain optical coherence tomography) on the large screen.

CONCLUSION

Diabetic eye disease can scare patients. If optometrists are able to educate their patients on the types of drugs and the advances in surgery that are used to treat diabetic eye disease, patients will feel empowered to follow up with a retina subspecialist to receive treatment in a timely manner.

- Nguyen QD, Brown DM, Marcus DM, et al; RISE and RIDE Research Group. Ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema: results from 2 phase III randomized trials: RISE and RIDE. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):789-801.

- The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Aflibercept, bevacizumab, or ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(13):1193-1203.

- The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network. Panretinal photocoagulation vs intravitreous ranibizumab for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(20):2137-2146.

- Anti-VEGF Treatment for Prevention of PDR/DME. clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02634333. Accessed March 21, 2018.